China’s Party Congress and the End of Political Competition

As the recent 20th Party Congress came to a conclusion, Sino-watchers across the globe were less interested in China’s immediate policy direction. Rather, there was a profound sense that the world’s second-largest economic and military power seemed to have gone adrift; or for some, more depressingly, it highlighted the end of an epoch.

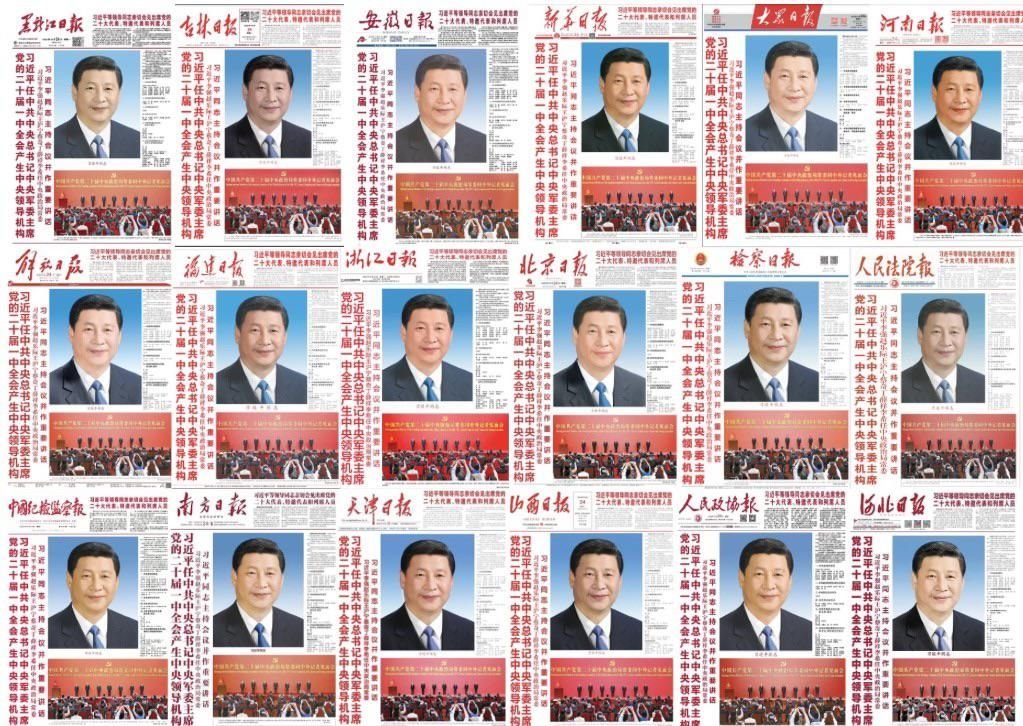

Image Credit: The Great Translation Movement

When the Chinese Communist Party’s National Congress concludes, it is a ripe time for many observers of Chinese politics to look at the new set of appointments and get a sense of the direction in which the country might be headed. Backgrounds of leaders elected to the Politburo Standing Committee (the highest decision-making body in the party) or the Politburo (the second-highest decision-making body) are revealed at the end of the Party Congress, and they would stay in power for the next five years. In Leninist-Marxist regimes, these leaders–who have historically been mostly men– are the living embodiment of the ‘five-year plans’ that rule planned economies.

However, as the recent 20th Party Congress came to a conclusion, Sino-watchers across the globe were less interested in China’s immediate policy direction. Rather, there was a profound sense that the world’s second-largest economic and military power seemed to have gone adrift; or for some, more depressingly, it highlighted the end of an epoch. The idea that China’s President Xi Jinping would dismiss a series of informal norms and stay in power for a record third term was known from the day the last Party Congress concluded in 2017. However, back then, there wasn’t a profound sense of gloom regarding China’s future. During this intervening period, President Xi supplied a heady cocktail of bizarre, contradictory, and self-defeating set of internal and external policies. Which forced even the most charitable China observer to reconsider their views.

Under normal circumstances, at least in the post-Mao period, there would have been some internal backlash against Xi’s policy decisions. But Xi has systematically erased all opposing views from the party and its government. He has done so, through a perfect amalgamation of an all-encompassing anti-graft campaign and appointments of only his loyalists. Thus, killing the very mechanism which might have prompted the party into action, and unleashing a self-correcting process. The recently concluded Party Congress is the logical conclusion of that same process Xi undertook ten years ago when he was appointed the party’s general secretary, China’s president, and the head of the Chinese Military Commission. As Geremie R. Barmé says, “chairman of everything.”

Xi has marginalized every single opposition leader. The only criterion for membership in the Politburo or the Standing Committee is complete allegiance to Xi. Consider this: The new Chinese Premier, Li Qiang, has lately been seen as a controversial figure owing to his heavy-handed response to COVID-19 in Shanghai. But then, to see him as a controversial leader would be to miss the point. He did exactly what Xi wanted, and got rewarded. The value of loyalty is highlighted by how three members of the Standing Committee and the Politburo were former personal secretaries to Xi.

This doesn’t mean that the appointees don’t highlight Xi’s vision of China’s future; they do. But these leadership bodies were traditionally considered fundamentally political bodies, as they helped comprehend the underlying distribution of power in the party. They highlighted factional power-sharing arrangements, rising stars, and falling tigers. That is no longer the case. In some ways, these bodies now mark the rather dramatic hollowing out of politics and political competition from the CCP. It is Xi Inc now.

“Rather than a moment of course correction, the 20th Party Congress sees the CCP […]cross a threshold into outright dictatorship and, with it, a likely future of political ossification, policy uncertainty, and the ruinous effects of one-man rule,” writes Jude Blanchette. Effectively, Xi has moved China from what Kevin Rudd used to refer to as an “enlightened authoritarian rule” to a personalistic dictatorship.

This is not to say that China ever had political freedoms, or it wasn’t a highly autocratic regime that used violence against its citizenry to the degree that it seemed like a mundane pastime. Former President Deng Xiaoping, who is considered the architect of China’s dramatic economic transition starting in the late-1970s, put in a logic of “collective leadership.” In essence, the idea had two core features: A reluctance towards a personality cult and sharing of power among different party factions, especially the Shanghai Clique and the Communist Youth League. Xi, with his personality cult and the complete marginalization of traditional factions, has put the principle of collective leadership to rest. Deng never adhered to this framework when he was in power. However, in the post-Deng era, this acted as a stable framework governing elite politics in the CCP. Until Xi got rid of it.

Both former presidents, Jiang Zemin, and Hu Jintao, were handpicked by Deng. Xi was the first CCP leader to have emerged out of Deng’s shadow. By 2017, when Xi had the first opportunity to dilute these informal norms of elite politics, he did exactly that. Thus, this Chinese “norms-based” authoritarian system worked only as long as its patron –Deng– or his appointees managed to monitor it.

Does this mean that the 20th Party Congress didn’t leave us with some clues about the future of China’s policy direction? That is far from the case. At the risk of oversimplifying, there were three clear takeaways.

First, most reform-minded politicians – such as Li Keqiang, Hu Chunhua, Wang Yang, Liu He, Guo Shuqing, and Yi Gang – have been side-lined from national leadership positions. This doesn’t necessarily mean that China won’t undertake reforms going ahead. It possibly will, but they would be less and less like the ones the West had anticipated, and more of Xi’s “Common Prosperity” and “Dual Circulation” variety. There was a broad expectation in the West that with time the CCP would embrace more market-based reforms, resulting in an economic order that resembles its Western counterparts. However, under Xi, the party has wrested back control of the economy, cracked down on big private conglomerates, and increased the party’s control over the decision-making process within private enterprises.

But as Yuen Yuen Ang points out, the problem with Xi’s idea of Common Prosperity is it wants to have the cake and eat it too. Xi wants to curb the excesses of a market economy and undertake more equal growth, which would necessarily involve some radical purging of monopolies and redistribution. While Xi is a proponent of the major crackdown, he also wants sustained growth, which is a contradictory objective. Structurally, China needs to transition to a consumption-based model, which it doesn’t seem to have the political appetite for. And regardless, the Chinese economy is staring at a prolonged period of growth slowdown, which would have substantial consequences for the global economy.

Second, new appointments point to a pattern of a rise of a new variety of technocrats who have a background in things in aerospace and other high-technologies. These members of the “cosmos club” have replaced the older technocrats who came from backgrounds in economics and finance. The technocrats from the past held significant positions in the State Council or key institutions like the Chinese central bank. Those technocrats were generally considered “reform-minded” and suggested that the Chinese economy would continue to undertake more market-based reforms over time. Now the rise of the “cosmos club” suggests Xi’s preference for these high technologies in China’s future economic model, as opposed to the more conventional market reforms.

Third, in Xi’s opening report to the delegates, he shifted China’s previous external posture, by not overtly referring to the global environment as conducive for “peace and development.” This concept was first formulated by Deng in the 1980s, and according to David M. Finkelstein, it implied that the world was at relative peace. Thus, given the remote possibility of war between China and other major powers, the former could focus on transforming its domestic economy. This was the guiding principle of China’s internal and external policies until Xi began to change it after coming to power in 2012.

Now, even the phrase – “peace and development” – has officially made way for a more cautious approach in the current “uncertain” times. Xi told the delegates at the Party Congress, “The historical trends of peace, development, cooperation, and mutual … [but]… the deficit in peace, development, security, and governance is growing.”

The biggest takeaway is simpler. The slowdown in China’s economy and rising big power competition have to some degree, been exacerbated due to Xi’s contradictory policies. The recent appointments at the highest party leadership levels suggest that Xi has created a domestic environment that is more conducive to such self-defeating policy decisions.

Srijan Shukla is pursuing a Master’s in International Relations at New York University. He studied Political Science and Economics at McGill University. He subsequently worked as a foreign affairs reporter for ThePrint.

Interesting and well researched article …..gives a wonderful overview of the latest dramatic and powerful political movements in China. These are important updates for all !!

Compliments to Srijan Shukla for an excellent analysis and professionally articulated writeup.