Obama in Cuba: The Eagle Has Landed?

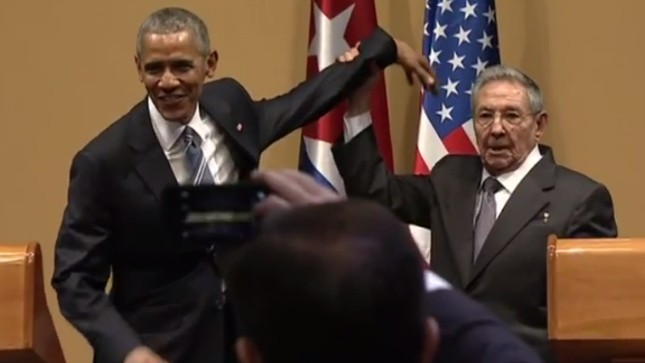

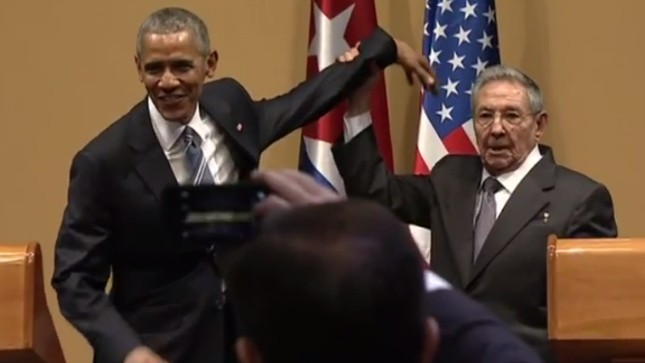

Cuban President Raul Castro, right, lifts up the arm of President Barack Obama at the conclusion of their joint news conference at the Palace of the Revolution, Monday, March 21, 2016, in Havana, Cuba. Picture by Ramon Espinosa | Associated Press.

In Havana, legend has it that a great symbol of US imperialism was defaced in January of 1961. Designed in 1925 to commemorate the U.S. sailors that lost their lives at the beginning of the Spanish-American war, the Monument to the Victims of the USS Maine was simple—two pillars joined with an arch crowned by an eagle, wings spread—and very American. But two years after the Cuban Revolution, the story goes, an angry mob took to the streets and knocked the eagle from its place. It stands that way today: two pillars reaching into the sky—nothing on top. A symbol of rebellion.

This story is analogous to the US-Cuba relationship since the turn of the century. The eagle that was removed in 1961 was actually the second version. The first iteration was violently set in flight by a passing hurricane one year after its installation. The Americans that built it must not have planned for stormy weather.

President Barack Obama is currently making history as the first sitting U.S. president to visit Cuba in 88 years. With a state dinner, a joint press conference, and more planned for this visit, Cubans and Americans hope this is the beginning of a new era. Certainly things are changing rapidly. But from what we’ve seen of the visit, the disconnect that plagued the relationship in the first place is once again bubbling to the surface.

At Monday’s press conference, President Obama challenged the Cuban regime on its human rights record, which if not improved would “continue to be a powerful irritant.” And he isn’t wrong. In its 2016 World Report, Human Rights Watch explains that Cuba “continues to repress dissent and discourage public criticism… [relying]less on long-term prison sentences to punish critics, but short-term arbitrary arrests of human rights defenders, independent journalists, and others have increased dramatically in recent years.”

But joining President Obama on stage, Cuban President Raúl Castro complained of U.S. double standards. He isn’t wrong either. The United States continues to turn a blind eye to human rights violations in Saudi Arabia. In the same report, Human Rights Watch writes, “Through 2015 Saudi authorities continued arbitrary arrests, trials, and convictions of peaceful dissidents.” And in the previous year’s report, the human rights agency explained, “During a visit to Saudi Arabia in March, U.S. President Barack Obama did not discuss human rights issues with Saudi officials.”.

For all the symbolic gestures of good faith to occur during Obama’s trip, in official discourse the United States and Cuba are still talking past one another. Cuba seems open to reestablishing relations with the United States insofar as they might spur much needed economic development. But Cuba still resists the United States’ tendency to impose concessions, and seeks to maintain a level of complete domestic authority that may not be viable in the relationship.

On the other hand, the United States seeks to promote major societal changes on the island. But this agenda has been imposed selectively throughout the world, undermining the notion of “universal values” that President Obama has alluded to during his visit. Not to mention, the idea that the United States is capable of imposing such an agenda in Cuba is not grounded in history. Recall this is the same country at the heart of the Cuban Missile Crisis, whose regime withstood the collapse of the Soviet Union, and resisted U.S. influence in spite of a major trade embargo for nearly 60 years. If either country really hopes to form a new and meaningful relationship, these attitudes must change. Even an end to the economic embargo, something President Obama has promised will happen, may fall short.

There is a great deal of fanfare surrounding this visit, and for good reason. Americans and Cubans alike sense change on the horizon. But when it comes down to it, both must draw from lessons of the past. Havana must recognize that relationships with superpowers are a tricky business. And sadly, the reality is the United States will never see Cuba as an equal partner in the relationship. The United States, however, stands to gain from granting the resilient island nation a little more respect. That’s not to belittle the human rights issue. On the contrary, greater progress is perhaps more likely if not seen as an imposition from the north.

What’s left of the eagle that adorned the USS Maine memorial is divided in two resting places. The U.S. Embassy houses its head. The Havana City History Museum stores its body and wings. Longtime foreign service officer Wayne Smith told the custodian of the museum that until the parts are reunited, relations between the United States and Cuba will be strained. Perhaps this has more truth in it than Smith intended.

Dylan is a first year M.A. student in International Relations. He graduated magna cum laude from the University of San Diego in 2013, with a B.A. in International Relations & Spanish. His primary areas of interest include human rights, rule of law, and political and economic development in Latin America. Some of his prior research experiences include working for the University of San Diego’s Trans-Border Institute analyzing rule of law in Mexico and U.S.-Mexico relations, and traveling to Nicaragua as a USD Changemaker Scholar to pursue his senior thesis. Dylan has traveled extensively throughout the region including stints in Chile, Mexico, and Guatemala. He is a passionate writer, and enthusiastic to be a part of JPI.