Who gets left out when literacy declines in the US?

Two men sit read books as they sit in chairs in a Barnes & Noble in Princeton, Mar. 15, 2006. (AP Photo/Mel Evans)

In 2025, 40 percent of American adults did not open a book. This is not because books are out of fashion, but rather because Americans are struggling to read. According to the National Literacy Institute, 130 million Americans are unable to read a story to their children. That represents roughly a third of the population that also struggles with reading and comprehension skills.

In 2024, 21 percent of U.S. adults were found to be functionally illiterate, a condition in which individuals possess basic reading and writing skills but struggle to apply them effectively in everyday situations. According to the National Literacy Institute, 54 percent of adults presented a literacy level below a sixth-grade level. Since 2017, the literacy rate in the U.S. has fallen by nearly 10 points.

Reading, however, is an integral part of our everyday life, from the ingredient list at the grocery store, the name of subway stops, to the weather forecast. Individuals often feel ashamed or embarrassed due to their reading struggles. They often avoid reading aloud or increasingly rely on memory rather than the provided written information. It is difficult for an illiterate individual to partake in basic social and civic activities. These struggles become particularly burdensome in political matters. Therefore, the decline of literacy has grave implications for how Americans navigate their everyday lives and how they approach politics.

What literacy means and how it is measured

Literacy is commonly defined as the ability to read and write, but more accurately, it encompasses the comprehension, evaluation, and utilization of information across varied fields such as health, financial, and legal matters.

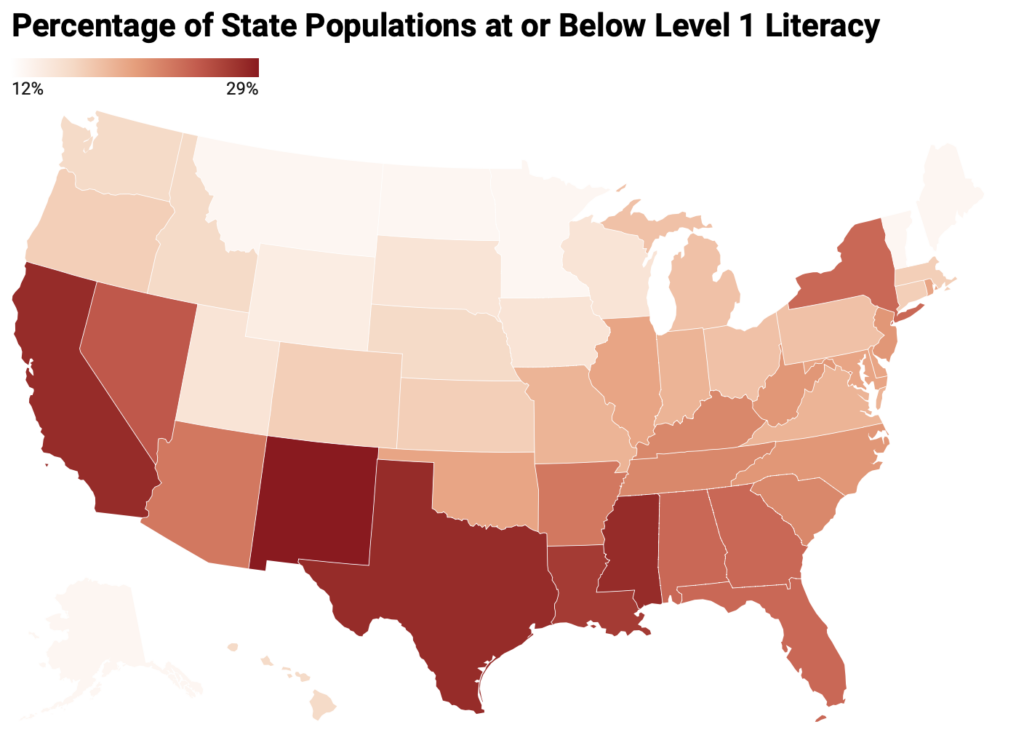

The National Center of Education Statistics measures adult literacy on a scale from 0 to 500, and categorizes results into five levels reflecting different proficiency skills. Level 1 represents the lowest level of literacy proficiency. Adults in this range have difficulty reading and understanding materials. Those at the higher end of Level 1 can perform simple tasks based on the information they read. Adults below that threshold, which includes one in every five adults, may only understand basic vocabulary or be functionally illiterate.

Chart creation: APM Research Lab | Data: PIACC

A state with an average score between 226 and 275 is classified as Level 2. This suggests that the average person in that state can decipher between a given text and information, such as paraphrasing or making low-level inferences. States with a score above 275 rise to Level 3, meaning the average person can identify rhetorical structures and evaluate pieces of information.

Chart creation: APM Research Lab | Data: PIACC

State differences and geographic inequality

Although the U.S. literacy rate is ranked 38th among countries worldwide, the national average masks stark differences among states. Data shows that Southern states have lower literacy rates than any other region. Louisiana, New Mexico, Mississippi, and Texas have the lowest child literacy rate in the country, averaging less than 254 points.

According to APM Research Lab, the ten counties with the highest percentage of adults at or below a Level 1 literacy are located in Texas, primarily along the US-Mexican border. The researchers attribute this partly to the high population of immigrants whose first language is not English. Additionally, they point out that poor reading skills correlated with poverty and limited access to resources.

Dr. Iris Feinberg, associate director of the Adult Literacy Research Center at Georgia State University, referred to these communities as a “print desert.” In these areas, there are few public signage beyond local stores, a few libraries, and bookstores. Even with widespread web access, people in these communities still struggle to use the internet due to their difficulties with spelling and reading.

In comparison, the highest literacy rates with scores above 278 are found in Massachusetts, Maryland, and New Hampshire. This reflects longstanding patterns of educational attainment and support. While economic resources and education funding play a role in shaping opportunities, from early childhood literacy programs to K–12 instructional quality, research shows that the relationship between federal and state funding and literacy outcomes is multifaceted. Outcomes depend not just on the amount spent, but on how resources are directed, how early interventions are structured, and how socioeconomic disadvantages are addressed.

Economic consequences of low literacy

The societal effects of low literacy extend beyond education. Low literacy levels are estimated to cost the United States up to $2.2 trillion per year through lost productivity, increased health care costs, higher unemployment rates, and greater reliance on social services.

Furthermore, the two challenges, literacy and poverty, are often interlinked. In impoverished regions of the world, educational opportunities are frequently scarce and exacerbated by the necessity for struggling families to prioritize immediate income over sending their children to school.

The lowest literacy rates are found in developing countries, predominantly those in South Asia, West Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. A similar pattern can be found in the U.S., where states with fewer financial resources present the lowest literacy level, reinforcing cycles of economic disadvantage.

Literacy and political participation

The most profound consequences of low literacy can be seen in politics. Political texts frequently use technical language, borrowed words, and complex sentence structures that require active reading and advanced comprehension. Individuals with limited reading skills often struggle to access and understand political information.

As a result, people with low literacy increasingly rely on audio or visual forms of information. In the digital age, podcasts, videos, and social media are becoming more accessible sources of political content. However, these formats also have limitations. According to the Reuters Insititute’s Digitial News Report, people worldwide are turning away from news, citing overload, distrust, and disengagement.

On social media platforms, traditional news outlets struggle to compete for attention. CNN and the New York Times, for example, rank behind public figures such as Elon Musk, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump in follower counts on X. This highlights the difficulty of translating print journalism into short-form digital content, which often only receives seconds of attention.

Many of the more detailed reports on political matters remain primarily in writing, making them inaccessible to readers with low literacy. As a result, individuals who are illiterate become alienated from political processes.

Another obstacle for people with low literacy levels in interacting with politics is voter registration. Registering to vote and completing a ballot requires both reading and comprehension of written instructions. For individuals with lower literacy, these steps can be intimidating and burdensome, discouraging political participation altogether. In her research on the political benefits of adult literacy, Professor Nelly Stromquist of the University of Maryland found that increased literacy correlates with a greater willingness to engage in political processes and advocate for community needs.

Looking ahead

Literacy is a foundational skill for a productive daily life. It is needed in every aspect of modern society and is essential for political participation. Being able to read and comprehend written words allows citizens to understand their rights, evaluate political claims, and engage in democratic processes.“Every page a child reads is a step toward their future,” said Dr. Ingrid Haynes-Taylor. “Literacy doesn’t just teach letters—it teaches possibilities.” The same holds for adults. Addressing declining literacy is not only an educational challenge but a democratic imperative. A democracy depends on citizens who can read, question, and decide for themselves. As literacy declines, so does the public’s ability to hold power to account.

Sina Amberg (she/her) is a first-year M.A. candidate in Political Science with a concentration in Political Economy. She earned her B.A. in Political Science and Law from the University of Zurich and the National Chengchi University. Her academic interests include resource allocation, societal change, political behavior, and development studies. She is also deeply committed to humanitarian action, demonstrated through her volunteer work with the Circle of Young Humanitarians.