The Last Nuclear Treaty Standing: How New START’s Expiration Poses a Strategic Dilemma for Asia

President Donald Trump and Russia's President Vladimir Putin arrive for a press conference at Joint Base Elmendorf- Richardson, Aug. 15, 2025, in Anchorage, Alaska. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

The expiration of New START on Feb. 5 serves as a test of whether nuclear strategic stability can endure when nuclear arms control is in dire straits. The treaty remains the last legally binding limit on the United States and Russia’s nuclear weapons stockpiles. In February 2023, President Vladimir Putin announced Russia would suspend participation in the New START, further hollowing out the last major verification framework shaping the world’s largest nuclear dyad. Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Defense reports that China is dramatically increasing its nuclear arms capacity. The strategic nuclear dynamic among the top nuclear powers is therefore shifting from a largely bilateral to a more complex trilateral environment in which transparency darkens just as Chinese capabilities accelerate.

If New START expires without a credible successor, the United States and Russia will enter a new phase without a binding, verification-backed ceiling on their deployed forces; the first since the Cold War era. The most immediate consequence will be the erosion of legibility—the shared visibility that prevents deterrence from collapsing into worst-case scenario guesswork. In that fog, the safest bureaucratic posture becomes the most dangerous strategic habit: assuming the worst. And the fog will not just obscure the West; it migrates toward the Asia-Pacific, where coercive signaling, crisis instability, and hedging pressures are already intensifying. Together, New START’s “death” and China’s buildup could make the Asia-Pacific the theater where great-power rivalry meets live contingencies, casting doubt on the viability of contemporary nonproliferation norms.

The Guardrail Explained: What is New START?

Since 1970, the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) has served as the cornerstone of the nuclear order. Shaped by Cold War fears of escalation and proliferation, the NPT sought to prevent the exacerbation of nuclear dangers. In this context, New START constrained the most consequential categories of U.S. and Russian strategic forces while also embedding transparency practices designed to reduce reliance on deterrence strategies. At its core, the treaty performed two central functions. First, it established enforceable ceilings on deployed strategic nuclear warheads and bombs that narrowed the range of plausible worst-case scenarios in force planning. Second, New START made those ceilings verifiable by pairing numerical constraints with a monitoring and verification system that included regular data exchanges and notifications, national technical means, and up to 18 short-notice on-site inspections annually. While the treaty did not create perfect trust, it institutionalized predictability, reducing incentives for surprise or breakout behavior, and raised the likelihood that significant noncompliance would be detected.

The erosion of New START did not occur in isolation. What began as a pandemic-era inspection pause in March 2020 gradually became entangled with a broader collapse of geopolitical trust, and disputes over resuming inspections intensified as U.S.-Russia relations deteriorated after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. By the time Moscow announced in February 2023 that it would suspend participation, arms control had already become a neglected priority; neither side is currently negotiating a follow-up treaty. In strategic terms, the treaty’s decline follows a familiar pattern: as uncertainty grows, worst-case planning becomes more attractive, and faster, riskier postures gain bureaucratic appeal. The issue for nuclear disarmament going forward is both quantitative and epistemic: understanding how leaders interpret an adversary’s capabilities and intent in moments of crisis, and how they expect the adversary to read their own posture.

The broader setting is also shifting. China’s rapid nuclear expansion complicates what had long been a primarily bilateral stability framework. Yet, Beijing has resisted joining trilateral arms-control talks on the grounds that its arsenal remains far smaller than those of the United States and Russia. Russia, for its part, has signaled that any future framework should account for all leading NATO countries’ forces, including French and British nuclear weapons, underscoring how difficult a negotiated successor will be. In international relations more broadly, the primary risk is a shift from rule-bound arms control like the NPT toward ad hoc arms management, where restraint depends more on short-term political choice than on durable verification.

Contingent Consequences: Asia-Pacific Dynamics in a Post-New START Order

As strategic stability becomes less institutionalized, risk is exported outward—particularly to the Asia-Pacific, where crisis flashpoints are already common and where many actors rely on increasingly shaky U.S. extended deterrence while confronting a rapidly modernizing China. In this environment, the central question for states like the Republic of Korea (ROK), Japan, and Taiwan is not whether they can replace New START, but how they can adapt to a nuclear order that is becoming less predictable.

The Republic of Korea: Hedging in the Fog

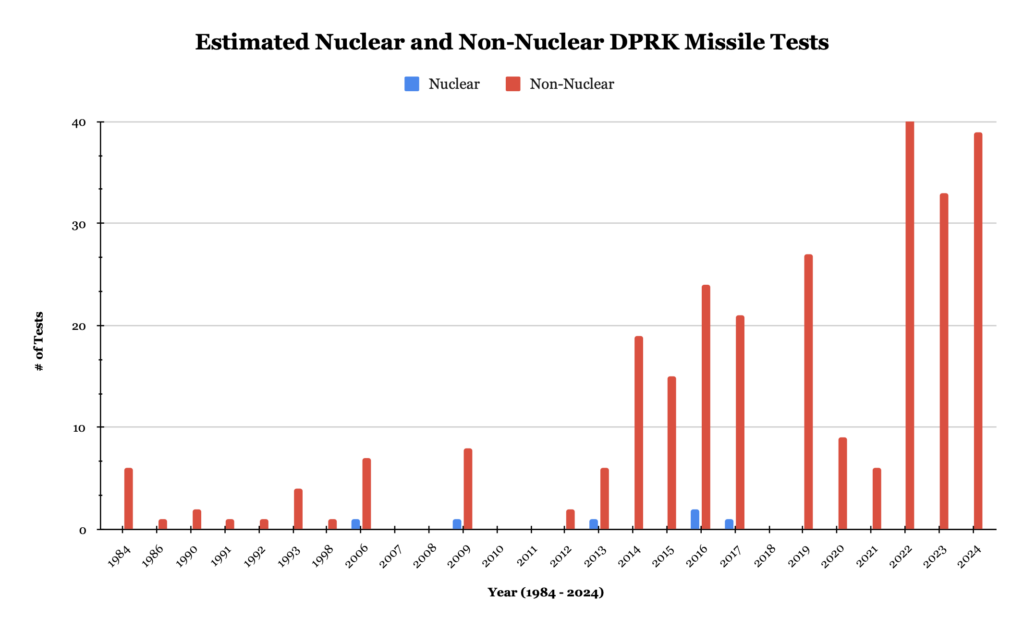

The ROK sits at the sharp end of nuclear politics without possessing nuclear weapons. It faces a nuclear-armed Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) and relies on U.S. extended deterrence to manage escalation risk on the peninsula. Against this baseline, long-run patterns in DPRK missile activity from 1984 to 2025 – as captured in the graph below – are more consistent with sustained capability development than episodic provocation.

Recent tests reinforce that trajectory. In January 2025, the DPRK test-launched an upgraded solid-fuel hypersonic intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM), which state media cast as “globally significant,” and in January 2026, Kim Jong Un oversaw additional hypersonic missile test flights just as South Korean President Lee Jae Myung departed for a state visit to China. The strategic environment has grown more complex since Russia and the DPRK signed the June 2024 DPRK-Russia Comprehensive Strategic Partnership Treaty, which includes a mutual-defense clause – signaling that any serious conflict involving the DPRK could draw on Russian support and complicate allied planning.

In this context, further erosion of constraints and transparency in U.S.-Russia nuclear relations is politically salient in Seoul. As Pyongyang’s alignment with Russia deepens, worst-case reasoning predominates. The domestic backdrop sharpens this sensitivity: the 2025 ASAN Institute polls reported a record-high 76.2 percent support for indigenous ROK nuclear weapons capabilities. Since 2023, Washington and Seoul have sought to make extended deterrence more concrete and politically “visible” through the Washington Declaration and the creation of the U.S.-ROK Nuclear Consultative Group (NCG). Yet, President Lee’s visit to China this month—during which he publicly requested Chinese President Xi Jinping to play a mediating roleon the Peninsula—also signals a parallel impulse to stabilize ties with Beijing, particularly on economic and regional-management grounds. In other words, a less constrained arms-control environment could raise the priceof security for the ROK. As February 2026 approaches, the key question is whether Seoul responds primarily by thickening alliance reassurance mechanisms or whether perceived uncertainty widens the political space for more consequential hedging debates, including renewed nuclear interest and greater reliance on China-channel diplomacy.

Japan: Deterrence Signaling as Strategic Legibility Erodes

Tokyo does not face an immediate nuclear-armed adversary on its border in the same way as the ROK, but it sits adjacent to multiple escalation-prone flashpoints while relying on U.S. extended deterrence to deter both nuclear and conventional coercion. Japan’s own defense assessments describe an increasingly severe threat environment, including a more imminent DPRK missile threat, expanding Chinese military activity, and the broader erosion of regional order. These pressures are likely to become more politically explicit under Japan’s new prime minister, Sanae Takaichi, whose government has assumed a sharper stance on China and Taiwan. Recent events between China and Japan illustrate a central feature of Tokyo’s problem: deterrence in Northeast Asia increasingly unfolds under conditions of coercive signaling and economic retaliation in addition to military posturing. A less transparent great-power nuclear environment compounds that challenge by making escalation boundaries harder to infer—and therefore harder to manage effectively in moments of crisis.

Japan and the U.S. have moved to operationalize reassurance through structured alliance mechanisms, recently announcing guidelines to deepen extended deterrence coordination. However, these mechanisms do little to eliminate doubt as the underlying strategic balance is evolving faster than reassurance procedures. Japan’s defense planning must respond to adversary modernization and higher-tempo coercion, while also dealing with uncertainty over whether U.S. commitments in the region will remain operationally coherent. In this insecure and less constrained nuclear environment, Tokyo is incentivized to develop some measure of deterrence capacity. This poses a serious break from past policy; while Japan’s long-standing non-nuclear posture remains firm, interest in a conversation about nuclear capacity is growing. In this context, New START’s approaching deadline adds an additional stressor for Japan on alliance reassurance and crisis stability in a region where coercive signaling already pushes the threshold of escalation.

Taiwan: Crisis Stability Under a Nuclear Shadow

Taiwan’s nuclear predicament is defined less by its own capabilities than by the nuclear relationship between the U.S. and China, which views unification with Taiwan as a core interest and increasingly relies on nuclear signaling to deter U.S. and allied intervention. Taiwan neither possesses nuclear weapons nor plausibly seeks them in the near term, given historical U.S. pressure and domestic constraints. The result is a security environment where conflict over Taiwan would unfold under an overt nuclear shadow that Taipei cannot control. From this vantage point, New START’s expiration represents the erosion of regional nuclear legibility at the very moment U.S.-China competition is sharpening. The thinning of U.S.-Russian transparency, combined with China’s growing arsenal, complicates Washington’s calculus about the nuclear risk of a Taiwan contingency. For Taipei, this deepens an already difficult question: how credible are U.S. security commitments when Washington must simultaneously manage escalation risks with two nuclear peers and worry about opportunistic moves by Moscow?

Taiwan’s likely objectives center on crisis management and conventional deterrence rather than nuclear acquisition. Policy debates and external analyses increasingly emphasize a ‘porcupine’ approach—building forces that are hard to disable, able to survive an initial strike, and capable of imposing costs at range—to raise the costs of aggression without relying on nuclear threats. In parallel, Taipei is investing in civil defense and economic resilience against blockades and cyberattacks, recognizing that nuclear-backed coercion may aim to paralyze society rather than immediately escalate to large-scale war. These measures are complemented by efforts to tighten coordination with Washington to ensure that public messaging and military signaling do not inadvertently suggest goals—such as regime change—that could trigger Chinese nuclear brinkmanship.

The key risk for Taiwan in a post-New START environment is the potential for escalation through ambiguity rather than deliberate nuclear use. As transparency frays and confidence in understanding each side’s thresholds declines, the danger that one side misreads routine signaling as preparation for a decisive move increases. Caught between competing risks yet lacking its own nuclear leverage, Taiwan must navigate a narrowing space for controlled escalation management under a nuclear shadow it did not design and cannot influence.

The Costs of Strategic Uncertainty

New START’s approaching deadline next month tests whether strategic stability can survive without binding limits and credible transparency. The immediate danger in the Asia-Pacific is not an automatic arms race, but strategic drift—a world where verification fades, worst-case assumptions become common, and coercive signaling becomes more frequent.

Even if Washington and Moscow achieve a stopgap arrangement, short-term constraint is not the same as long-term stability. Russia has floated a one-year extension of New START limits, while U.S. debate has focused on whether informal adherence can buy time. But reported numbers without verification do not rebuild confidence. They produce a thinner form of restraint that can easily unravel under stress, leaving Asia-Pacific middle powers watching for concrete risk-reduction measures rather than declarations of intent. More importantly, even a U.S.-Russia agreement would not address the central driver of Asia-Pacific anxiety: China’s nuclear trajectory and its refusal to join trilateral arms-control talks. For regional states, this means the strategic balance may continue to shift even if U.S.-Russia relations temporarily stabilize. That is also why today’s uncertainty extends to the future credibility of nonproliferation and disarmament regimes. The NPT review process has struggled to convert shared concern into enforceable political momentum, and current efforts are lagging behind the strategic reality.

In the months ahead, analysts should focus less on rhetoric and more on observable indicators of whether the ‘nuclear fog’ is thickening – or if new stabilizers are emerging. Key questions include whether U.S.-Russia measures can restore verification habits, whether China displays any movement on risk reduction even absent formal talks, and whether 2026’s nonproliferation diplomacy can still anchor restraint in a more contested strategic environment. Ultimately, the world is entering a more dangerous nuclear order: one in which miscalculation is easier, coercive signaling is incentivized, and hedging pressures are harder to contain. When the last guardrail fails, the Asia-Pacific is the most likely arena where great-power uncertainty will collide with active flashpoints, and where local decisions could trigger global escalation dynamics. In a less legible nuclear order, stability will not be inherited. It will be rebuilt—or gambled away.

Hana Kim is a second-year MA candidate in International Relations at NYU, concentrating in Asian Studies. She earned her BA in International Studies with an emphasis on Global Politics from Pepperdine University in 2023, where her thesis explored the implications of US censorship on Japan-ROK relations. She has previously interned at the Global America Business Institute, researching international civil nuclear energy policy. Currently, Hana serves as a policy intern at The Korea Society, focusing on US-ROK cooperation and NE Asian affairs. Her interests include East Asian security, alliance diplomacy, and US foreign policy in the Asia-Pacific. After graduating, she plans to pursue a career in foreign policy, advancing resilient US-Asia relations.