For Jay Rosen, American Press Needs to Become More Pro-Democracy

In June, Jay Rosen retired from NYU, but he remains an active media critic. Credit: Courtesy of Jay Rosen.

The Washington Post is amid the worst crisis of its history; public media has been severely defunded; and CBS has new leadership and ownership poised to shift the broadcaster’s political philosophy. The landscape of political news is changing rapidly. At a time when journalists are questioned by both the White House and the public, the Journal of Political Inquiry speaks with Jay Rosen, retired professor of journalism at New York University. One of the country’s most prominent media critics for decades, Rosen is deeply concerned about the state of the field.

You have been a media scholar and critic for the last 40 years. Is this really the worst time for journalism?

Absolutely. There’s no comparison, partly because it’s the worst time for American democracy, but also because the threats to freedom of the press are greater than ever.

We have a government that describes journalists as “enemies of the people.” Nothing has ever even been close to that. American presidents didn’t talk like that. They had frustrations with the press and criticisms to make, but calling journalists “enemies of the people” is just way out there.

The most striking thing about it is that it’s likely to get worse. We’re not through it. We don’t know if there’s a light at the end of the tunnel. The tunnel just keeps getting bigger.

We know from other countries that one of the first things that happens in an authoritarian slide is an attack on the press

This is President Trump’s second term. Was the media industry once again not ready? Were there no lessons learnt from 2016?

I think it’s really hard for the news industry to learn anything. I wouldn’t say there was no change, but there was every reason to believe two years before the 2024 election that he was going to run. We knew that he would use an attack method to describe journalists as “enemies of the people,” that he would lie frequently and without shame, and that he would make an issue of the 2020 campaign and deny what happened.

What we didn’t see was people in journalism looking at those facts and concluding that this was bigger than anything they had ever done. They didn’t have the tools. To this day, they don’t really see it: “Why do you mean by the tools? We covered the campaign.” From their point of view, they did their job.

I began saying, along with many other people, to the American press: “You have to learn how to become more pro-democracy.” We know from the experience of other countries that one of the first things that happens in an authoritarian slide is an attack on the press. I decided to reduce my message to the American press down to the smallest, most direct unit that I could come up with, which was: “Not the odds but the stakes.”

The “odds” is a reference to who’s going to win. What’s likely? What do the polls say? That is typical of the kind of political coverage we got. And “stakes” is a reference to consequences. What are going to be the consequences if Trump returns in 2025? Everybody in the press knew it was going to be a really different guy in the president’s office if he won in 2024.

This slogan did circulate around the press, but also in public discourse. It wasn’t a major development at all; it was sort of a very minor thing, but it was an expression of my frustration. And of course, it didn’t change anything.

The Washington Post, one of the most respected newspapers in the country, just laid off 300 employees. How does that fit into the broader context?

It’s mind-bending to think that you can’t fund the newspaper of record in the capital of the richest country in the globe. It just seems crazy. This is a very important institution. It shouldn’t shrivel up like that and be treated the way it has been by its current owner. There’s a lot of frustration because the leaders of the Post basically had no idea what they were doing.

During the period last year when the Washington Post got smaller and smaller as Trump’s second government went along, the leaders set what they called the Big Hairy Audacious Goal: 200 million paying users. The New York Times, the undisputed industry leader, has 11 million subscribers. The Post, the Times, Politico, and Axios combined don’t reach 100 million monthly viewers, and that includes people who aren’t paying. It was not a serious path.

The Post has been neglected by its owner, and it’s been misdirected by its leadership.

That can be measured in what happened in the critical moment when Bezos decided not to support the Democratic candidate, even though the announcement was already written up and ready to be published. 250,000 subscribers canceled. That’s a lot of people.

It has been a downward spiral since then.

Bezos put himself closer to Trump, and that sent a signal. It was a shock and an incredible turn of events. It really is the worst part about this whole thing.

Jeff Bezos has been the Post owner since 2013. For some years, he was widely understood to be quite hands-off.

This is one of the most amazing things in the whole story. Not only was he considered hands-off, but he was basically hands-off all the way through this crisis as well. He doesn’t go to the newsroom and say: “Here’s the story I want you to publish” or “You can’t report that.”

What he did in the case of the 2024 election is exert his will on the opinion side of the Washington Post, but he’s never done that for the newsroom. At least he obeys that principle. It gives you a little bit of hope, but there are so many things on the other side that give you no hope.

I would like to see Bezos give a one-time gift to create the Washington Post Foundation

The Post lost 77 million in 2023 and 100 million in 2024. What would you say to the people who claim that changes needed to be made in a business that was not viable?

One answer to that is it shouldn’t be a business. It is more of a public good, something that has to exist, but is unlikely to be there unless you make special provisions for it. Maybe we have to start thinking about the Post more as a non-profit. That doesn’t solve everything, though. You still have to support it.

Another answer is that these shifts from 900 people to 600 people to 300 people are bad for the culture of the Washington Post. Leadership should have been aware that if it had to shrink in order to meet what revenue is, then it would have had to act sooner. In Jeff Bezos’ position, most business people would say: “We have to at least break even. You have to at least not tax all of my money every year”. That’s a good policy. If you didn’t have something like that, it would lead to a lack of seriousness and commitment to get as much revenue as you can.

Another possible way to get out of this situation is for Bezos to give an endowment, a very large hunk of money that stays there permanently. The interest is what you use to run the newsroom. If anyone could figure it out, that would be an innovation in supporting journalism.

What I would like to see him do is give a one-time gift to create the Washington Post Foundation, the purpose of which would be to publish the Washington Post and make sure that it can’t be affected by its next owner, because there is no owner. That is what we call in another language a trust. But there are so many difficult variables here. The most difficult thing is that billionaires are unpredictable. We have no idea how he thinks about this. The number of sentences out there from Bezos about the layoffs is maybe five or six.

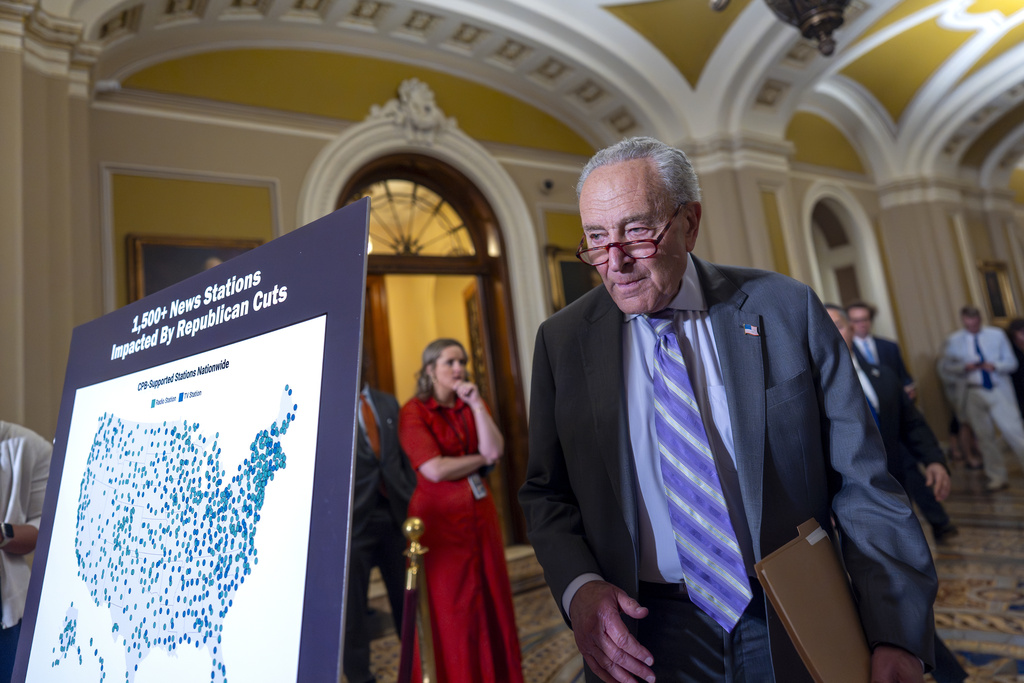

In July, the Republican-led Congress decided to rescind $1.1 billion in funding to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which decided to dissolve as a result. What has been the impact on public media?

NPR has come out of it surprisingly strong. That’s been good to see. They’re not going to disappear or be crippled by this event. The member stations that are part of NPR’s network are the ones that have the most problems surviving because many of them are smaller. They often have small communities with a small degree of funding. Almost all the funding came from the government.

The whole network is less powerful than it once was, less independent, and there’s more gloom about it. One of our two political parties saw that it was in their interest to kill it. They determined that a weak press was better for their party.

The Republican Party has wanted to do away with the subsidies for a long time. It would come up before Congress from time to time, but it never won, even when they controlled the government. There is a reason for that. In some small places around the United States, NPR was the only broadcast media available for the representatives to talk to their voters.

But this time, Trump had in so many ways triumphed over his own people that nobody wanted to go against his campaign to convince every American that the press is the enemy of the people. That is an agenda item of his, and he’s done very well on it.

What is your assessment of Bari Weiss’ leadership of CBS so far?

Being the editor-in-chief of a network like CBS, up until this year, has been one of the most important jobs in the media, usually given to somebody who’s been there for a long time, learned different types of things doing different jobs, and had tremendous respect from other people.

That kind of person is no longer in charge of CBS. Now it’s somebody who’s never reported a story in any medium. Who has worked in the media, yes, in the opinion pages of the New York Times, and thanks to her own ingenuity, she’s been created as a publisher of her own little 150,000 people publication.

She is not seen as editor-in-chief for CBS because of her extensive experience in international reporting, in local journalism, in investigative journalism, or in broadcast, which is an art in itself. Aside from the content, just knowing how broadcasting works is a huge area of knowledge. If she doesn’t have any of those things, what does she have?

She’s there to change the ideology of CBS. This is particularly tricky. If we go to very experienced people in CBS, and ask what the political philosophy of CBS is, they are going to say, “We don’t have a political philosophy, we are just journalists.”

I don’t know how long she’s going to be able to remain in her job. But I strongly believe that the kind of problems and revolts that she’s cooked up so far are going to continue. She’s there to upset and overturn what has always been the case. She’s got a big job and a little resume.

The powerful will find ways to be informed. The question is whether publics, in plural, will continue to be informed

Looking into new business models for journalism, Semafor comes to my mind. They get a big part of their revenue from the events they organize and corporate sponsorships. Is this a winning model?

Every succeeding digital news property is an island of its own, which makes it difficult to answer questions like that.

Semafor figured out a model that, at the beginning, was not something they thought was going to be central to their site. They are developing the model of live journalism quite skilfully, and it is working for them. But it isn’t something that can work for everyone else. Everyone who is doing well in digital journalism has solved the riddle for themselves. You can’t assume that this is what’s going to work elsewhere.

There are things that we are learning that are useful, like a niche that you can own or a need that you serve that nobody serves. Or profit from who you are or what you’ve done in the past, what authority you have for earlier projects. We don’t have a formula. Each news site has to discover for itself how to work for its community. There are sites like Axios or Politico that are not really for the public as much as they are for different professions. You can see why it would be easier to fund the model that would work for a narrower audience like that.

I’m not concerned that the managerial class of the world is going to be left without news sources in the future. The rich and powerful people will find ways to be informed. The question is whether publics, in plural, will continue to be informed.

The New York Times is one of the very few media outlets that keeps growing, but is this concentration of power into one newspaper bad for the ecosystem?

It may be that we’re heading towards a world where you only have one big national news source, like the U.K. with the BBC. But I think it’s important to have competition. We need strong newsrooms of different kinds. The New York Times is great, but it’s one idea of national journalism. I don’t like this whittling down to one or two newsrooms; we need more than that.

It is amazing how well the New York Times has managed to steer between these events. One of the reasons is that they came up with a very simple way of knowing if you’re doing your job, which is: “journalism worth paying for.” It is both a statement about the journalism and the business model. It seems incredibly simple, it is, but it was just at the right time when everybody was saying, “Okay, how are we going to continue to survive?” Okay, we’re going to give you the answer. Are you ready? Subscriptions.

They are also very serious about understanding their audience and getting really good at it. In a digital world, you can have very good information about your audience. You can track what people are doing when they come to your site. You have a lot of data about how people sift through the news.

What would you say to aspiring young journalists who see this world that you just described to us?

I think it’s worth it. There’s always going to be journalists because it’s a great need. For some people, it’s the most exciting thing they could think of. It’s very hard for authoritarian governments to keep people from doing journalism. Even though they can make it really, really difficult, journalism is going to go on.

JPI’s Editor-in-Chief and a second-year Global Journalism graduate student. He is a reporter, fact-checker, and audio producer specializing in international relations, human rights, and culture. His work has been featured in Foreign Policy, the Spanish Public Radio, and Verificat, among other outlets. He has been recognized with the Overseas Press Club Foundation Scholar Award and the ‘la Caixa’ Foundation Fellowship.