Obligatory democracy is no democracy at all

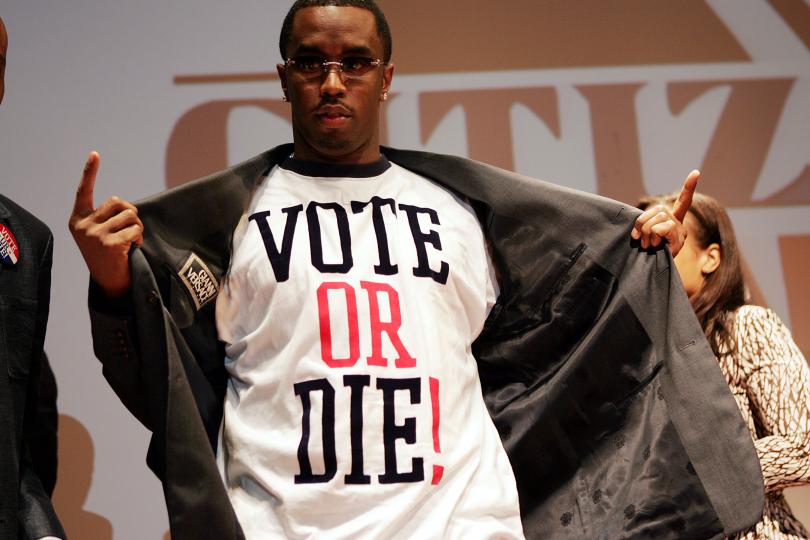

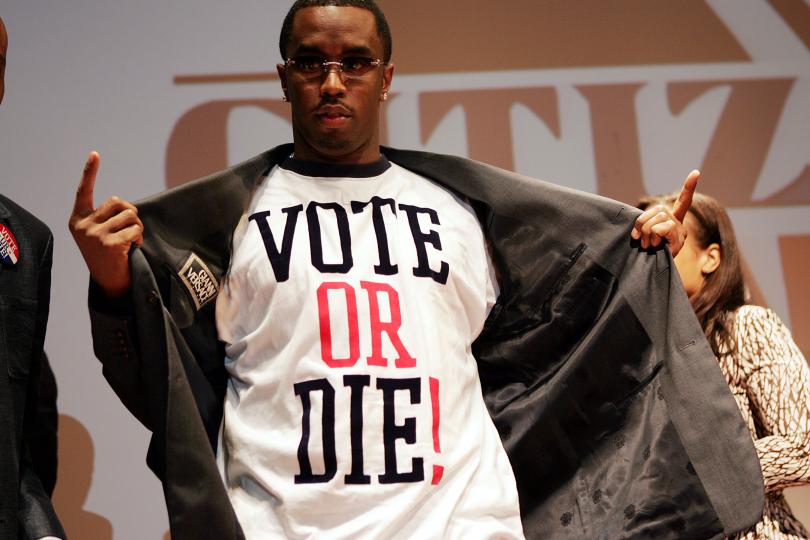

Picture by Scott Gries | Getty Images.

When asked to govern themselves, it appears most Americans would rather do other things. Local elections rarely pull more than 30 percent of constituents to the polls. Congressional and state elections fare little better. Even the stream of media chatter that hangs around every presidential election fails to get Americans to the polls: on average, only 60 percent of eligible citizens show up on Election Day. The American civic energy that inspired Alexis de Tocqueville to write “Democracy in America” in 1831 has congealed into an apathetic slush.

Enter Australia, where on average 94 percent of the voting population turns out for national elections. 94 percent. If Tocqueville had been alive to see this, he would surely have written another book on “Democracy in Australia,” right?

Maybe not. Australians are required to vote by law and pay fines if they abstain. This arrangement makes it difficult to understand the motivations behind their behavior—are Australians driven to the polls by the national policy debate or out of concern for their personal finances?

During his time in America, Tocqueville saw that the cause of democratic behavior is just as (if not more) important than the behavior itself. He wrote of an American public that did much more than mechanically fulfill the requirements of self-government. He wrote of a people that felt like citizens, that took pride in their government and were happy to bear the responsibility of democracy. Not only did they vote, they read newspapers, talked politics at dinner, and developed nuanced views on the proper relationship between a citizen and the state. In short, they had developed a democratic culture.

What he saw in America stood in stark contrast to his French homeland, a country that had been brutalized and divided by its own experiments in self-government. France’s shots at democratization were quickly followed by other types of shots—the kind propelled by gunpowder and accompanied by the guillotine. Both countries saw the emergence of a politically active citizenry. In one case, it came with bitterness and division. In the other, it precipitated the establishment of a durable democracy shaped by compromise.

“Habits of the heart” separated the American success from the French failure. Americans possessed a democratic spirit: a pride in being a part of this governing experiment, a belief in the dignifying power of democracy, and an appreciation of the importance of compromise and reasoned debate. The important implication of “Democracy in America” is that stable democracies require a strong, pervasive civic culture—that even the most brilliant institutional arrangements are not enough.

Compulsory voting is just such an institutional arrangement. It was a policy designed by elites to shepherd the people into fulfilling the requirements of democracy. Tocqueville might note that, these requirements, no matter how faithfully fulfilled, are meaningless absent a sincere public desire to contribute to the democratic project.

But perhaps to compare modern Australia to early 19th century America and France is to be misguided by theory. Governments, after all, must focus on practical matters, and the benefits of the Australian system are well known. To start, a larger voting pool generally means more moderate government. In the United States, people with extreme political beliefs are the ones most invested in the political process. They tend to vote in higher numbers than moderates, increasing the likelihood that stubbornly “principled” (i.e. allergic to compromise) politicians take office. This can make governing, which requires compromise, difficult.

The inability to compromise compromises governing effectiveness, as Americans who follow the shenanigans in Congress are well aware. The same deficit in civic engagement that leads to low voluntary voting can lead to a polarized and ineffective government. Ineffective government further erodes the civic ethos that drives larger turnouts; still fewer voters take the trouble to vote the next time round, and the end result is a vicious cycle of dysfunction and disillusionment

Compulsory voting seems like the obvious fix to this bind. It gets more people to the polls, meaning the winner is more representative of the collective will. And because a larger electorate tends to elect more moderate representatives, government runs more smoothly, thereby building up the perceptions of legitimacy that promote civic involvement.

But this seemingly clean solution overlooks some of the fundamental causes of low voter turnout, and allows them to fester. If we accept Tocqueville’s claim that democratic citizens are indispensable to a healthy democracy, then compelling those citizens to partake in the democratic process is akin to forcing a child to attend Sunday church, and then praising the youth’s pious discipline. The problem is that coercing short-term changes in behavior can erode the values that motivate people to engage in that behavior independently. Perhaps the least devout aren’t those who ditch Sunday service, but those forced to attend, mechanically moving their lips as everyone around them sings. Using external pressure to boost democratic electoral authority and democratic effectiveness carries the same risks as pushing children into church every Sunday: they’ll go, but joylessly, only when you’re around, and likely leave no less invested than when they arrived.

From its beginnings, democracy has been an experiment—a pristine philosophy paired with a most earthly implementation. Maybe the philosophy is too elevated, taking its cues from superhuman ideals and glossing over the difficulties of human interaction. Maybe human beings aren’t capable of coercion-free self-government.

If so, shortcuts like compulsory voting may be our best hope for maintaining at least a spectre of self-rule. But democracies that compel participation are hollow—finely functioning bodies without souls. A democracy that resorts to compulsory voting has made a grim compromise: it has chosen to preserve the outer form of democracy by abandoning the spirit.

Andrew Tripodo studies American political theory at NYU and teaches high school civics at Democracy Prep Public Schools in Harlem. His research focuses on the relationship between citizens and the state in democratic governments.