A Brief History of the US Labor Movement

The first national federation of unions, the National Labor Union, was created in 1872 after workers demanded for an eight-hour workday. In the following decades, unions representing an assortment of trades and demands sprang up across the US. Their goal was to protect the rights – to safety, humane conditions, and social and economic freedom – of workers as booming corporations seemingly sought to eliminate them.

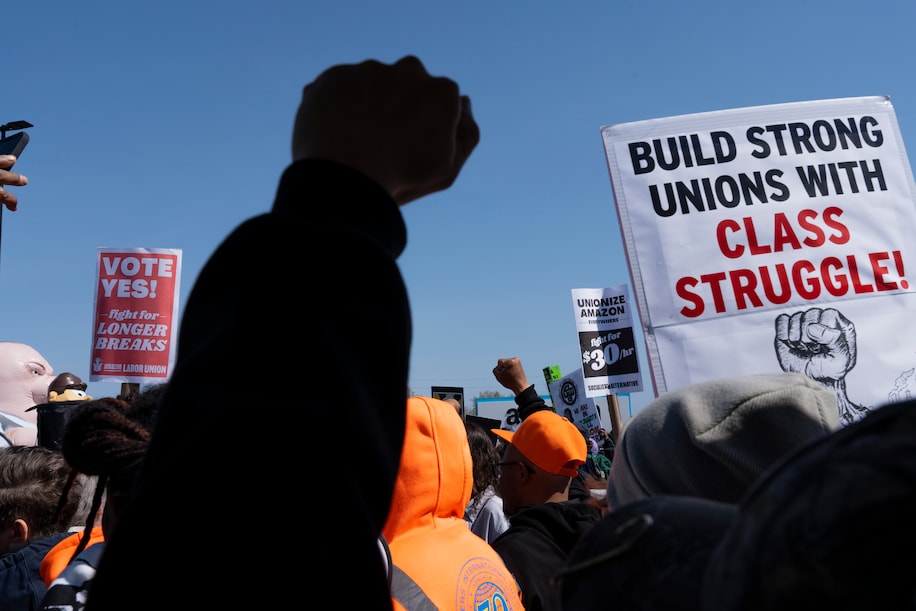

Image Credit: Calla Kessler for The Washington Post

The first national federation of unions, the National Labor Union, was created in 1872 after workers demanded for an eight-hour workday. In the following decades, unions representing an assortment of trades and demands sprang up across the US. Their goal was to protect the rights – to safety, humane conditions, and social and economic freedom – of workers as booming corporations seemingly sought to eliminate them. Historian Howard Zinn outlines the rise of unionization during the late 19th and 20th centuries in his book, A People’s History of the United States: 1492-Present. But what exactly were the conditions that led to the emerging US labor movement of the late 1800s and early 1900s?

A new kind of labor union was formed in Chicago on June 27th, 1905. Two hundred “socialists, anarchists, and radical trade unionists” from across the country gathered to form the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), or commonly nicknamed the “Wobblies.” This new organization would be more inclusive than its predecessors; workers of various races, sexes, and trades would be welcome, following its slogan of “One Big Union.” During that first convention the opening words proclaimed by William D. Haywood were decisive and inspiring: “This is the Continental Congress of the Working-Class. We are here to confederate workers of this country into a working-class movement that shall have its purpose the emancipation of the working-class from the slave bondage of capitalism.” The IWW’s approach – that uninhibited solidarity would be the strongest weapon for laborers – was “an immensely powerful idea” according to Zinn.

One driving force for the formation of the IWW was the unfettered growth of the imperialist-capitalist system in the late 19th century. Zinn summarizes how after the bloody and expensive Civil War, the US experienced an industrial boom where “ . . . steam and electricity replaced human muscle, iron replaced wood, and steel replaced iron . . . Machines could now drive steel tools. Oil could lubricate machines and light homes, streets, factories. People and goods could move by railroad, propelled by steam along steel rails . . . The telephone, the typewriter, and the adding machine speeded up the work of business.” This period became known as the Gilded Age starting in the 1870s where the economic system of capitalism seemed to be performing really well, but not for everybody. Around this time economic growth created a 48% rise in wages, but it was spread out unequally, so the benefit of rising wages did not reach most people. A growing lower class of people who lost their livelihoods to industrialization and overpowered corporations started to question the capitalist system that was seemingly failing them. Historian Jaime Caro-Morente explains how “Society started to ponder that there was some error in their system or some corrupting factor altered it. The individuals and society as a whole began to suspect that republican-democratic political culture was not functioning correctly.” This evidently sowed discontent among the working class which would only grow in the following years.

In 1898 the Spanish-American War broke out when the US joined Cuba in its fight for independence from Spain. From the start the US was interested in a free Cuba because of the economic possibilities of increased trade and business opportunities with the island. Many US citizens empathized with the Cuban revolution, recalling America’s fight for independence over a century ago. So, when in February 1898 the US battleship Maine sank in Havana harbor due to still-contested circumstances, the US used the opportunity to join the war. Despite heavy public backing and the full force of yellow journalism, not all Americans supported the decision. Zinn explains, “American labor unions had sympathy for the Cuban rebels as soon as the insurrection against Spain began in 1895. But they opposed American expansionism.” Bolton Hall, the treasurer of the American Longshoremen’s Union, published his opposition in “A Peace Appeal to Labor,” where he argued that working-class Americans will fuel the war with their bodies and taxes but they will not see the rewards of victory. Still, after war was declared most unions went along, and victory did indeed bring higher employment levels and wages, but also higher prices and taxes.

It also increased America’s lust for capitalist expansion. Once the war ended American companies moved in quickly to take over railroad, mine, and sugar properties in Cuba. The US also annexed Puerto Rico and Hawaii in the following years, and made attempts in the Philippines. But where it made moves amongst one class, capitalist expansion was increasingly frowned upon by another. During the US’s campaign for the Philippines the Anti-Imperialist League circulated more than a million writings of opposition. The immorality of capitalist imperialism led to a wave of unpatriotic sentiment amongst the working class and minority populations. A few years after the Spanish-American War, anarchist and feminist writer Emma Goldman spoke about the fallout: “How our hearts burned with indignation against the atrocious Spaniards!… But when the smoke was over, the dead buried, and the cost of the war came back to the people in an increase in the price of commodities and rent—that is, when we sobered up from our patriotic spree—it suddenly dawned on us that the cause of the Spanish-American war was the price of sugar…. that the lives, blood, and money of the American people were used to protect the interests of the American capitalists.” During Theodore Roosevelt’s 1899 speech “The Strenuous Life,” he argued that Americans must rise up to the difficult task of bringing about a better world. But labor activists increasingly wondered why it was their duty to spread “righteousness” and “high ideals” to other nations if workers in the US didn’t even receive those values.

At the same time, business expansion gave rise to deteriorating working conditions for ordinary laborers. In 1906 Upton Sinclair published his novel The Jungle which revealed the dismal conditions of meatpacking plants in Chicago, leading to calls for regulations. Other famous anti-capitalist writers of the time such as Jack London, Theodore Dreiser, and Frank Norris published to wide audiences. Zinn outlines how the flourishing start of the century started going downhill for businesses and laborers alike: “The process of business concentration had gone forward; the control by bankers had become clearer. As technology developed and corporations became larger, they needed more capital, and it was the bankers who had this capital . . . But even [J.P.] Morgan and his associates were not in complete control of such a system. In 1907, there was a panic, financial collapse, and crisis.” The biggest businesses were not hurt as much, but for the most part capitalists saw their profits falter and their industries stall. In response, they searched for new ways to cut costs, further pushing the envelope on poor labor conditions. One emerging system was called Taylorism, which aimed to increase productivity by breaking jobs down into simple, monotonous tasks. This allowed for more unskilled and interchangeable jobs fit for the growing immigrant population. Many found themselves working in dangerous auto factories or battered sweatshops. The anti-capitalist sentiment was also spreading worldwide, with historian Robert Marks noting that “ . . . revolution was shaking not just Russia but other parts of the world as well in the years before and after World War I,” such as with the Mexican Revolution, the overthrow of the Manchu Dynasty in China, and the rise of Benito Mussolini in Italy during the early 1900s.

The encroaching capitalist–imperialist system and business expansion at the expense of labor conditions pushed workers towards unions. Two major unions – the Knights of Labor (1869) and the American Federation of Labor (1886) – preceded the IWW, but they were wrought with ineffective leadership, insufficient benefits, and failed to create a unified front of workers. One union, the Western Federation of Miners (WFA), sought to expand its reach, so they decided to form an alliance with the Socialist Party of America (SPA) and its popular leader Eugene V. Debs. This alliance came together in 1903 with the creation of the American Labor Union, which two years later would become the IWW.

The formation of the IWW was a huge step forward for labor unions, but it’s crusades were often in response to tragic events or had tragic outcomes, such as the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Company fire in 1911. Even in the aftermath, Zinn outlines the prevailing conditions: “There were more fires. And accidents. According to a report of the Commission on Industrial Relations, in 1914, 35,000 workers were killed in industrial accidents and 700,000 injured.” Worsening conditions turned more workers towards the union, and strikes continued across the country.

Zinn describes how unions faced “all the weapons the system could put together: the newspapers, the courts, the police, the army, mob violence.” Laws were created for the specific purpose of trampling the workers’ movement. Lawyer and author Ahmed White outlines how legislation such as the Espionage Act was used to target socialists and IWW members, including Eugene V. Debs who was sentenced to ten years in prison in September 1918 (he would later have his term commuted after two and a half years by President Warren Harding). Socialists “ . . . were the largest contingent of the 1055 people convicted of violating the Espionage Act during and just after the First World War. Also convicted were about 200 members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW),” mostly leaders within the organization. The purported function of the law was to “criminalize interference with war production or the draft,” but it was evidently stretched to fit accusations related to socialism or labor unions. This wasn’t surprising since many supporters of socialism and members of the IWW were also against capitalist expansion and the war effort.

In addition to the Espionage Act, White mentions how criminal syndicalism statutes were utilized by businessmen in an assortment of industries to “ . . . criminalize the promotion of ‘industrial’ or ‘political’ change by means of ‘sabotage,’ ‘terrorism,’ or other forms of violence, including by means of mere membership in an organization said to be committed to such a program.” Thus, being simply a member of the IWW or having any association with the Communist Party became a crime. To make matters worse, the Red Scare that was sweeping America between 1919-1920 induced extreme anti-communist sentiment, and by extension anti-socialism and anti-unionization sentiments.

The labor unions also faced a more devious opponent: the Progressive party. Idaho’s anti-union law was first enacted under Progressive Governor Moses Alexander, and Minnesota’s push to criminalize the IWW was spearheaded by Progressive congressman John Lind. Although there were many examples of this, several Progressives did oppose the laws. Still, it seemed the general direction and leadership of the party were not in support of widespread unionization. It is true that many governmental reforms were implemented during this time, such as the Meat Inspection Act, the Hepburn Act, and the Pure Food and Drug Act under Theodore Roosevelt and the Mann-Elkins Act and the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Amendments to the Constitution under Taft. Many states also passed laws regulating workers’ wages and hours, safety inspections of factories, and workers’ compensation, which undeniably improved the lives of ordinary people to some extent. But these reforms were mostly done reluctantly in order to quiet revolutionary movements that aimed to enact more systemic change. Even known “trust-buster” Theodore Roosevelt had two men from J. P. Morgan, Elbert Gary, and George Perkins, arranging “private negotiations with the president to make sure the ‘trust-busting’ would not go too far,” according to Zinn. Roosevelt’s belief was that these reforms would quell the unionists, communists, and socialists from pushing for more radical change.

To some extent this plan worked, but in general Roosevelt’s presidency did not stop the unions from continuing their strikes and demands — at least not immediately. Eventually, though, the momentum would fade. With time the conservative and progressive fronts, along with many union members and leftists being jailed or dissuaded through fear of incarceration, led to the dwindling support for the IWW. White concludes that “The IWW never regained the vitality it had in the late 1910s and early 1920s; and in the decades that followed, the Communist Party died as well, even after forsaking the idea of organizing its own unions.” In the following decades the advents of World War I and The Great Depression, culminating in FDR’s New Deal, would transform the labor movement into what continues on today.

Based on the economic and industrial conditions of the time, the worker’s revolution seemed like a natural and reasonable response to capitalist growth. The prior system of worker exploitation to meet the needs of unfettered capitalism/industrialization was unsustainable. Infinite economic growth could not coexist with limited human physicality and environmental resources, and a zero-sum economic system was unacceptable to laborers worldwide. Today, corporate power is much larger and more ubiquitous than it was in the early 1900s, and the power difference between corporations and laborers has expanded exponentially. Still, the labor movement persists with the assertion that with enough worker’s support and a strong organizational foundation, any reform can be accomplished. Even if that proves to be true, the modern fight for labor rights may require a new set of tools, and the fight of those before us may help lead the way.

Roya Lotfi (she/her) formerly held the role of Editor-in-Chief at JPI Online Magazine. Her academic journey led her to a Master’s degree in International Relations from New York University, complementing her earlier BS in Biology from Montclair State University. Despite her scientific background, Roya’s unwavering passion for domestic and international politics guided her toward the vibrant world of IR. Prior to commencing her studies at NYU, she honed her skills in video production while working at Bright Trip Inc. and even contributed her talents to NBCUniversal. Looking ahead, her ultimate career aspiration is to create captivating video content focusing on current events and international relations within a media journalism organization. During her leisure hours, Roya enjoys indulging in reading and leisurely strolls around Central Park.