Perspective | The Moral Myopia of Woke Culture

It says that anyone who doesn’t abide by every single aspect of woke dogma in the West is a slaver or a fascist. But those actual slavers and fascists in the Middle East and China? Well, who are we to judge? We detest our own society so much that we aren’t willing to accept that other places may be worse.

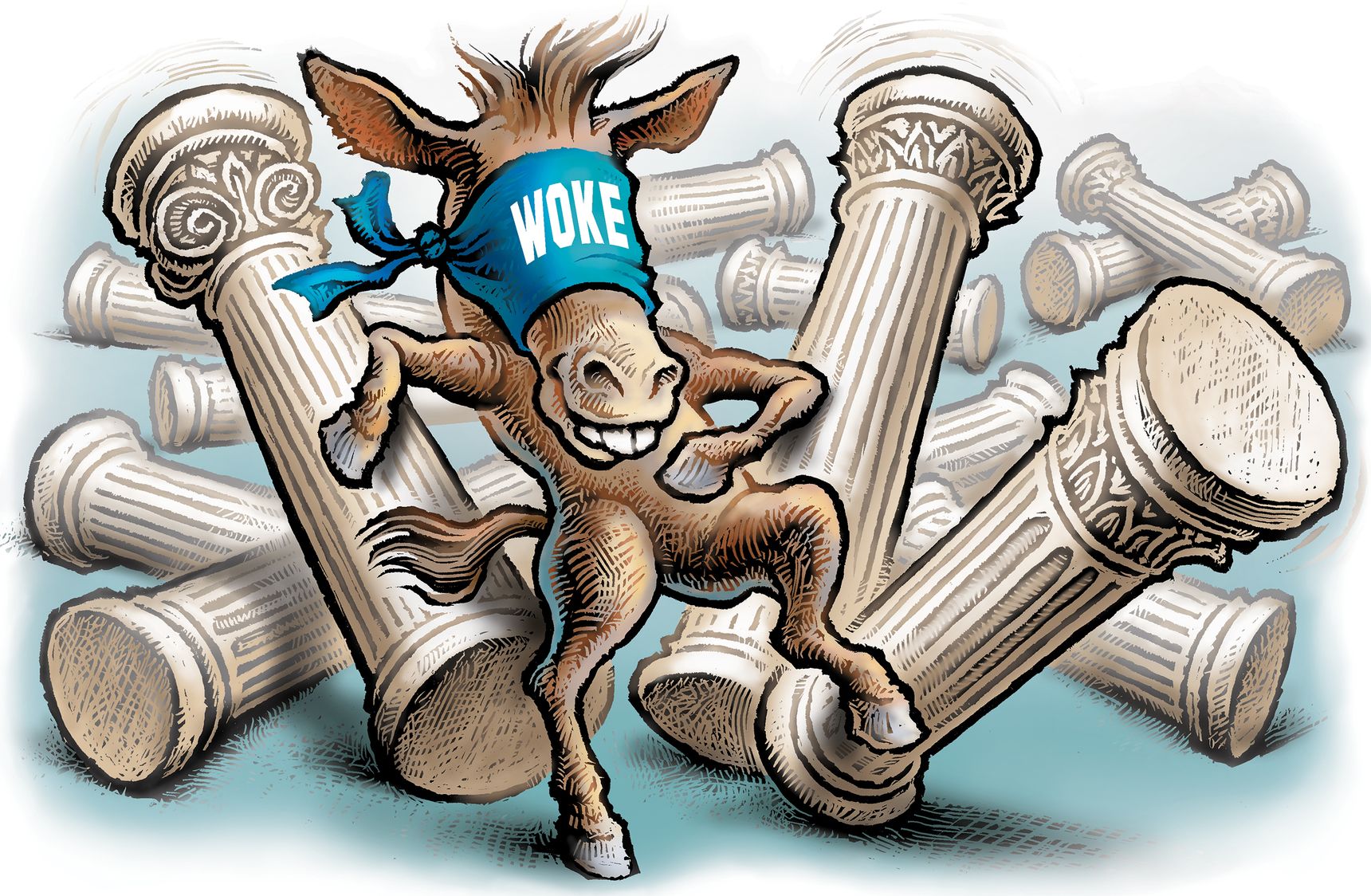

Image Credit: Phil Foster / The Wall Street Journal

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

These hallowed words of the Preamble to the Constitution of the United States, first learned in my Grade 9 history class, were my initial introduction to American politics. For a teenager born and raised in Cambodia, a country with people full of nationalistic fervor and a government that can do no wrong in the eyes of its citizens, I couldn’t help but admire the innate humility in the American spirit, to admit that their country will always be a work in progress, which is why they must continually strive “to form a more perfect Union.”

Having come to the United States at the age of 19, I started to think of it as my adopted country. But it wasn’t long before I recognized that the America I had yearned for so long was a shell of its former self. Everywhere I turned, I was told how intolerant this nation was. Every time I went online, I was bombarded with videos of intellectuals calling the Constitution “trash.” Every day my American friends talked about moving to a different country since they could not stand it here. By all accounts, I do believe that Americans regularly fight for valid and noble causes. But when I hear people here insisting that America is a great evil all the while being born in a country seeping with privilege that millions around the world would risk their lives to be a part of, I notice that the aspiration “to form a more perfect Union” has been twisted into wokeness.

What is wokeness?

To be woke, as defined in the Merriam-Webster dictionary, is to be “aware of and actively attentive to important societal facts and issues.” The term has its roots in Black communities and gained widespread usage around 2014, following the tragic police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. During that time, it assumed a haunting significance, emblematic of a commitment to vigilance against police brutality and unjust law enforcement practices. Then years later, the semantic trajectory of “woke” has morphed into a concise encapsulation of leftist political ideology, centered on social justice, intersectionality, and identity politics.

Undeniably, the tenets of woke ideology have bent the moral arc toward justice and prompted many Americans to confront the failings of past generations. “But in the focus on inequalities of power, the concept of justice is often left by the wayside,” as the philosopher and cultural commentator Susan Neiman writes in her latest book titled Left Is Not Woke.

“Wokeness demands that nations and peoples face up to their criminal histories,” Neiman argues, “But in the process, it often concludes that all history is criminal.” In other words, the essence of being woke is not just about being alerted to or informed about injustice anymore. It evolves into a meticulous scrutiny of every historical event, subjecting them to contemporary moral standards. This proclivity, in turn, propels a culture of wokeness toward a form of doctrinaire rigidity and fosters a lingering sense of generational guilt that tightly ensnares the collective consciousness of the nation, usually manifesting in self-deprecating sentiments.

The first 15 words of the Preamble to the Constitution of the United States are predicated on the idea of constructive self-critique, facilitating a discerning examination of various inequalities sculpted by historical wrongs. This ethos is the cornerstone of the exceptional nature of American society. Yet, the advent of wokeness signifies the regression of self-criticism into the abyss of self-loathing and detrimental guilt. It is mirrored in the changes in attitude from a healthy national confidence to a terminal uncertainty, and it brings about the shortsightedness exemplified by woke elites’ reactions to the predicament of oppressed people in other places around the globe.

Consider the following example: During the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing, J.A. Adande, the Director of Sports Journalism at Northwestern University, was asked how he could reconcile enjoying the games while China is committing genocide against Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang.

Here is what Adande said: “I think it’s standard in sport right now. You have to have a cognitive dissonance. You need to compartmentalize. […] And who are we to criticize China’s human rights records when we have ongoing attacks by the agents of the state against unarmed citizens, and we’ve got assaults on the voting rights of our people of color in various states in this country.”

At this pivotal moment, the United States finds itself enshrouded in an atmosphere dominated by internal apprehensions and anxieties, resulting in a trend toward cultural and intellectual insularity. It is as though the shining city on a hill is oblivious to the rest of the world, too busy battling its own demons to worry about others. Of course, should people like Adande insist on equating the flaws in our liberal democracy to the ongoing horrors in authoritarian regimes, is it surprising, then, that certain echelons of the American intelligentsia and commentary class remain indifferent to the broader global efforts against repression?

This nation still has a lot of room for improvement when it comes to police reform. And yes, there are complicated debates to be had here about voter ID law (which Adande referred to as “assaults on the voting rights of our people of color”). But acknowledging that says nothing about the reality that China is holding hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs in re-education camps. It says nothing about the fact that the CCP has a systematic program of beating, torturing, and raping these ethnic minorities today. And if we, as a society, have become impervious to that—if we despise ourselves more than we despise that—then we have come to the precipice of moral dereliction. Then we are defending the indefensible.

The ideology of wokeness presents notable challenges in addressing certain issues, largely due to its reductionist perspective. It interprets the world through the lens of identity-based power dynamics, wherein oppression is predominantly attributed to individuals who are perceived as white, male, able-bodied, heterosexual, and cisgender. Such groups are considered to possess societal privileges, and even in the absence of active discrimination on an individual level, they could still be deemed complicit in either benefitting from or perpetuating an oppressive system. Conversely, this framework posits that the oppressed are those individuals whose identities have historically suffered marginalization, namely people of color, women, those with disabilities, and members of the LGBTQ+ community.

This framework then sets up a hierarchical moral structure that allows people to accrue virtue in proportion to the perceived quantity or depth of their marginalized identity. For instance, a cisgender woman may be considered more oppressed than a cisgender man but more privileged than a transgender woman due to the assumed level of oppression associated with transgender identity. However, if the transgender woman is white, she may still be seen as more privileged than a black transgender woman because the black transgender woman embodies both racial and gender identity oppressions—thus, the quantity of her oppressed identities is greater.

The first problem with woke ideology lies in its failure to take its theoretical assumptions to their logical conclusion and accept that every person is endowed with a spectrum of advantages and disadvantages from birth. These factors are infinite and boundless in scope. Take, for example, the unspoken privilege of being raised in a household with two supportive parents—a facet conspicuously absent in the discussions promoted by proponents of woke ideology. Yet, the stability afforded by such an upbringing wields a formidable sway over one’s trajectory toward success, at times overshadowing the purported impact of factors such as race or gender.

Additionally, the determination of whether an individual’s identity confers privilege or marginalization is profoundly contextual. Just consider this: Although conventional wisdom within woke circles might posit that men inherently possess a greater degree of societal privilege compared to women, empirical evidence unveils a striking incongruity in the context of conflict-related fatalities. Surprisingly, men are disproportionately vulnerable to victimization, facing a 1.3 to 10 times higher likelihood of death compared to women. Yet, this aspect of male vulnerability continues to be overlooked by woke ideologues.

The second—and more pressing—problem with woke ideology revolves around its hierarchical moral framework. There, individuals and groups with a greater number of oppressed identities or identities characterized by deeper levels of oppression are heralded as morally superior, whereas those with presumed privileged identities are regarded as morally compromised. This paradigm is vividly exemplified in the notion of the regressive left—a term coined in 2007 by Maajid Nawaz, a former Islamist and activist. In his observations, Nawaz witnessed a pervasive moral myopia that permeated the emergent cultural and ideological movement, which would later come to be known as wokeness. Notably, he discerned a tendency among certain left-leaning individuals to abstain from criticizing Islam due to its association with people of color, while exhibiting a greater propensity to scrutinize Christianity, as it is commonly regarded as a “white” religion. This selective approach to criticism based on the racial or cultural background of religions demonstrates a shallow worldview that fails to apply consistent standards of analysis.

To illustrate this point further, we can turn to the case of Sam Harris, an American philosopher known as one of the “Four Horsemen” of New Atheism. Harris had long gained recognition as a vocal critic of organized religions; however, he became branded as a pseudoscientific racist only after he started critiquing Islam. In fact, Harris’ public notoriety as a contentious figure took root during a heated exchange on the satirical TV show Real Time With Bill Maher, where he found himself embroiled in a debate on Islam with actor Ben Affleck. It was during this exchange that the Hollywood star accused Harris of Islamophobia and racism, thus marking a turning point in the wider American public’s perception of Harris’ views.

Or consider this anecdote: Over the course of 2022, one of the topics I debated most with my American and European friends was pertaining to FIFA’s decision to award World Cup hosting rights to Qatar, a country where homosexuality is prohibited by theocratic law. A country where migrant workers involved in World Cup infrastructure projects faced delayed or unpaid wages, forced labor, long hours in hot weather, employer intimidation, and the inability to leave their jobs because of the country’s sponsorship system.

Presented with these facts, many of my friends’ attitudes toward the situation could be described as nonchalant at best, and their responses were, “Let he who is without sin cast the first stone!” and “We are hardly in a position to pass judgment when our Founding Fathers themselves were colonialists and slaveholders.” Interestingly, some even expressed sympathy toward Qatar’s laws and Islamic theocracy, citing the importance of “cultural respect and sensitivity” while in the same breath, they vehemently condemned Ron DeSantis’ “Don’t Say Gay” bill.

This kind of sentiment was further echoed in FIFA President Gianni Infantino’s nearly hour-long tirade against critics of the controversial tournament. There, he claimed: “What we Europeans have been doing for the last 3,000 years, we should be apologizing for the next 3,000 years before starting to give moral lessons.” It was then that I realized wokeness is not just a phenomenon unique to the United States; it has consumed the entirety of Western civilization.

Why do people in the West fixate so much on the misdeeds of our forefathers while largely ignoring the abuses and exploitations witnessed around the globe? It is because our hyperawareness of historical injustices compels us to seek out signs of oppression, despite its decline, at every corner of our society. And sometimes, the zeal to right the wrong of our past makes us nitpick every minor instance that can be deemed problematic, resulting in the nearsightedness of the world at large. For one thing, the rationale of wokeness usually follows this logic chain: In light of our own societal ills, what moral authority does the West have to admonish countries like Qatar? And if we have no right to lecture these autocratic countries, why should we refrain from vacationing in Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and luxuriating in amenities created by migrant workers enduring conditions tantamount to indentured servitude? Why should we abstain from enjoying the fruits of Uyghur forced labor in China by purchasing inexpensive goods?

Unfortunately, this logic normalizes tyranny. It says that anyone who doesn’t abide by every single aspect of woke dogma in the West is a slaver or a fascist. But those actual slavers and fascists in the Middle East and China? Well, who are we to judge? We detest our own society so much that we aren’t willing to accept that other places may be worse.

The fallacy inherent in this rationalization resides in the attempt to exonerate a moral offense by invoking the faulty character of the West. This is nothing new; it dates back to the late 1970s when any criticism of the Soviet Union was dismissed by referencing some of the West’s shortcomings. What distinguishes the contemporary milieu is the omnipresence of woke ideology within our major institutions, wherein we seem to have internalized these bad-faith critiques weaponized by whataboutism, rendering us myopic to matters beyond our borders.

People like me, who have lived outside the confines of the Western world, find ourselves at odds with the simplistic woke narrative that denigrates Western civilization as fundamentally ill-gotten. Our firsthand experiences lead us to recognize the progressive nature of the West in contrast to our respective homelands, thereby compelling woke elites to confront the reality of other countries. Yet, more often than not, they perceive our recognition as bolstering oppressive discourses of cultural imperialism, racism, and colonial power because they frequently regard the West as an exclusive civilization that has perpetuated a series of injustices.

Take Australian writer Van Badham, for instance. In 2018, she wrote that “the words ‘western civilization’ denote a racist colonial project to crush, change, enslave, eradicate or genocidally erase other cultures.” She went even further to say that “to ‘civilize’ is a verb that divorces people from the values of their own community and indoctrinates them into another’s. Historical rhetoric polarizes the ‘civilized’ westerner as superior to the dehumanized ‘savages,’ ‘primitives,’ and ‘barbarians’ of the term’s late 18th-19th century common use.”

This line of thinking has entrenched itself in our collective consciousness, giving rise to the expansion of conceptual boundaries. The once clear-cut definition of the term “Western” has undergone a deliberate dilution and is now susceptible to overuse by woke ideologues, who stretch its connotations to encompass notions such as “racism,” “oppression,” and “colonialism.” This characterization aligns with the tendency to define Western civilization by every negative cultural and political attribute that happened to emerge from the western part of the Eurasian continent.

Merely expressing endorsement for values that emanate from the Western tradition—which include civil rights, equality before the law, procedural justice, and liberal democracy—places people like me in the crosshairs of woke ideologues, who hastily condemn such stances as complicity in a purportedly vile system. They conflate our support of Western civilization with the propagation of white civilization’s supremacy, white nationalism, cultural racism, and colonialism. And therefore, we must be opposed at all costs. This argument epitomizes the precarious confusion that arises when one becomes too deeply submerged in the fervent currents of woke discourse, causing fundamental reasoning and moral bearings to be obscured.

Drawing from the same wellspring of strategy, the Chinese Communist Party and theocratic leaders of the Middle East can effortlessly undercut the struggle for liberty and civil rights among their dissidents by wielding “Western” as a derogatory epithet and accusing them of clandestine collusion with the West. Hence, when people here only see the West—and by extension, Western values—through the lens of wokeness, they demonstrate a skewed moral perspective that overlooks the flagrant transgressions of global tyrannies. Ultimately, they detract from the universal aspirations of these dissidents who yearn for the ideal of freedom—or in other words, their own “Western values.”

Contrary to what Badham believes, “to civilize” does not mean severing people from their community values and imposing foreign ones upon them. In fact, it means bringing them and their societies to a more advanced and progressive stage of social and cultural development. And Western values do just that. They are values that transcend race and culture, moving people toward progress, liberty, tolerance, and human dignity. Or as Ibn Warraq, an Islamic scholar and a leading figure in Qur’anic criticism, put it:

The great ideas of the West—rationalism, self-criticism, the disinterested search for truth, the separation of church and state, the rule of law, equality before the law, freedom of conscience and expression, human rights, liberal democracy—together constitute quite an achievement, surely, for any civilization. This set of principles remains the best and perhaps the only means for all people, no matter what race or creed, to live in freedom and reach their full potential. […] When Western values have been adopted by other societies, such as Japan or South Korea, their citizens have reaped benefits.

If the West, especially the United States, is to remain the heartland of the free world, the most urgent question we ought to ask ourselves is: how might we triumph in an ideological struggle against our adversaries when our dominant culture is so self-loathing?

We can’t. I once saw a quote by Russian-born American researcher Ariel Durant that said, “A great civilization is not conquered from without, until it has destroyed itself from within.” When a society loses faith in its own essence and principles, it teeters perilously on the brink of self-annihilation and collapse. All around the globe, countless people seek the freedoms that the West takes for granted. In the meantime, our refusal to see the monumental strides achieved over the arc of our history threatens to erode the very foundations that have rendered Western civilization the cradle and bulwark of liberal democracy, while sheltering the most egregious violators of human rights from rightful censure. In doing so, we inadvertently bolster the new Axis powers that are antagonistic toward the prevailing liberal world order, from Russia’s recent incursion into Ukrainian sovereignty to China’s overt ambition to subjugate perhaps the most vibrant bastion of liberal democracy in Asia—Taiwan, and the resurgence of Islamic fundamentalists in the Middle East fervently yearning to resurrect their caliphates.

Each time I reflect upon the Preamble, I am inevitably reminded of the boundless potential for progress within America. President Bill Clinton eloquently captured this sentiment in his inaugural address on January 20, 1993, “There is nothing wrong with America that cannot be cured by what is right with America.” This momentous speech is a reflection of a bygone era, a period during which the United States still envisioned itself as the vanguard of the free world. Its artistic creations, literary works, and overall cultural influence, akin to the arrow of history, guided our collective voyage toward the coveted road of rectitude. And yet, a prevalent sentiment pervading America today is one that appears detached from the notion that progress is attainable. It manifests as a landscape fraught with tension and imbued with deep pessimism—edging toward nihilism. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

The path to “a more perfect Union” is not paved with guilt or shame. It is paved by our fortitude to stare at our moral and practical shortcomings in the eyes and repair them. It is paved by our resolution to retain the capacity to combine self-criticism with self-affirmation, demonstrating pride in what we have done and will continue to do.

Jay Sophalkalyan is a cultural critic and political analyst whose work explores the fraught intersections of politics, technology, and identity in the modern world. Formerly the Deputy Editor-in-Chief of JPI online magazine, he now writes regularly for Nikkei Asia, The Dispatch, Quillette, and other outlets, with a focus on digital censorship, post-colonial realism, and the creeping authoritarianism of both East and West. Born in Cambodia and raised across continents, Jay brings a transnational lens to his writing—rooted in classical liberal values and honed by a principled skepticism of ideological excess. He earned his master’s degree in Experimental Humanities from NYU in 2024, specializing in journalism and political theory. His Substack, Thought Criminal, is a defiant and measured response to the soft totalitarianism of our age.

The woke see only so far. The bad word. They do not understand that there are some good people, and some very bad people who are in the bad word. They have been taught that all in the group are “good” people, much maligned. They, in their child-like condition, believe this. Yet, it is not true. There are many in the maligned culture who are criminal, and who are committing crimes. The Woke believe these people should get a pass, whatever crime they have committed, because they are in the maligned group.