The Uniting Power of Trump’s Immigration Policies

Since the 2016 U.S. election, the Trump administration has tried to keep its campaign promises by making refugee entry into the U.S. as difficult as possible. Instead of driving a wedge between U.S. citizens and immigrants, these strict policies are uniting different American organizations fighting for immigrant rights, and encouraging wide-spread civic engagement.

“That’s the great thing about Trump, that he brought a lot of immigrant communities together and a lot of non-immigrant communities have supported the immigrant movement, who prior to that haven’t paid any attention to immigrant rights,” said Ninaj Raoul, president of Haitian Women for Haitian Refugees.

Asylum Cases in New York City

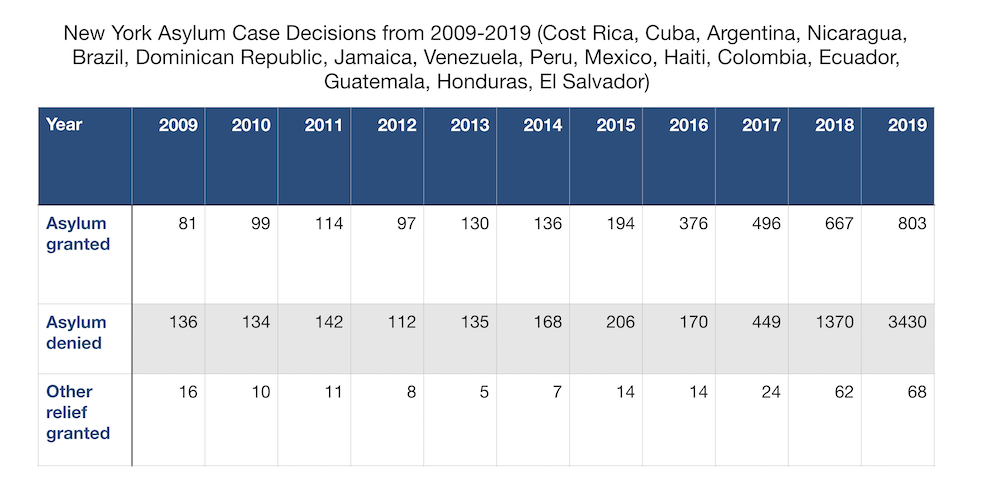

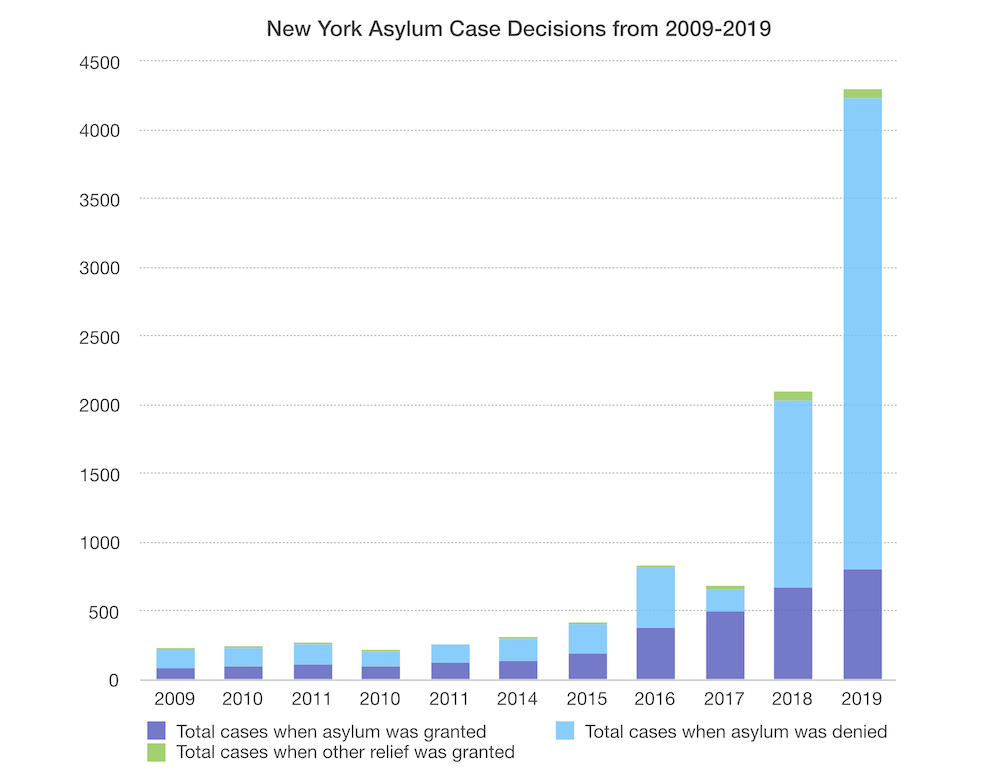

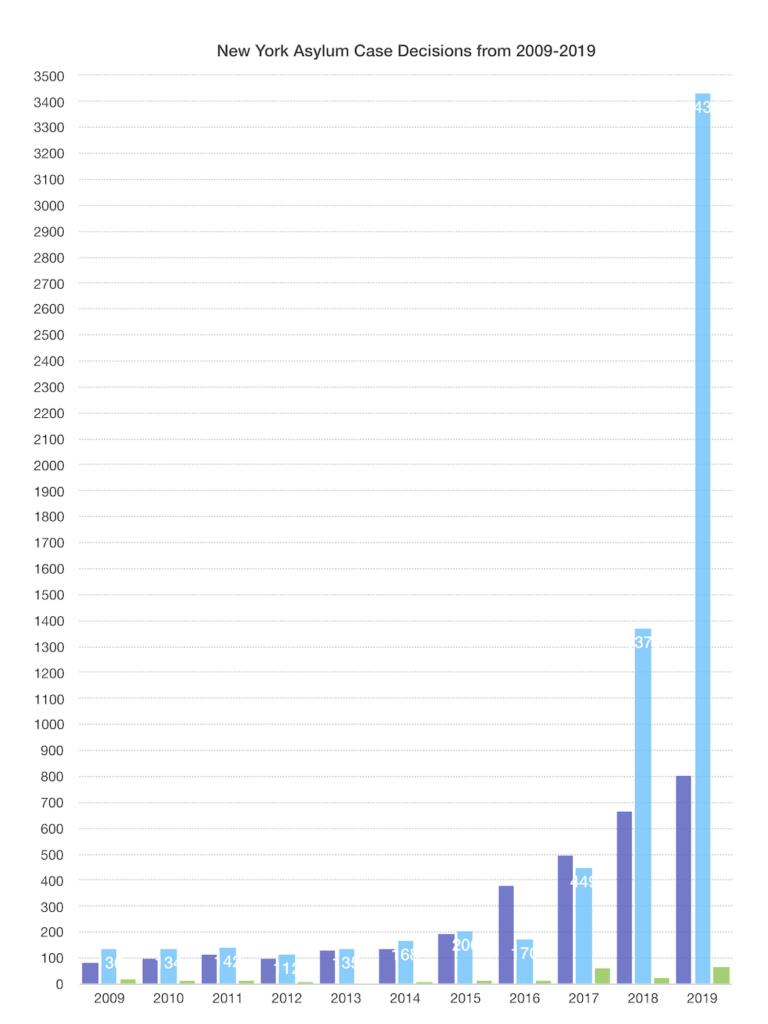

TRAC Immigration data shows that during the Obama administration, 30 percent of asylum cases were granted in New York, which sees the highest number of asylum cases in the country. These percentages have steadily fallen since 2016, reaching an all-time low in 2019 of about 16 percent. Reporting from the Washington Post demonstrates that the annual number of refugees accepted into the United States has fluctuated between 70,000 and 80,000, reaching an all-time high of 110,000 during the Obama administration. This month, however, President Trump set a cap of 18,000 accepted refugees for 2020, the lowest since 1980 during the Carter administration. This follows a series of policies enacted to curb immigration, including a 2017 removal of the priority designation for women with children.

Trump has placed a particular focus on limiting immigration from Latin American nations. The graphics below illustrate how the number of accepted and denied asylum cases from 16 Latin American countries have changed from the Obama administration to the Trump administration. The data show that while asylum requests rise each year, the number of acceptances has gone down drastically; however, the denied asylum cases have risen steadily.

The Immigration Crisis Beyond Asylum

This dramatic change in the legal system is not accidental, and reflects a series of changes within the Trump administration to curb immigration. Over 300,000 people have been affected by the recent attempted terminations of Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for people from Haiti, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua and other countries formerly eligible for TPS. In 2017, the administration announced that it would end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), or the “dreamers” program, which allowed young undocumented immigrants to live in the country without fear of deportation.

Celina Marquez and Mark Priceman work for the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Migration and Refugee Services department, and assist with resettling refugees once they’re allowed to cross the U.S. border. Marquez, who focuses on women and children seeking asylum, recently traveled to the border regions of Juarez and El Paso. “We are one of nine organizations throughout the country that helps resettle refugees. Since 1980 about one third of all resettled refugees have come through our organization,” Priceman said. However, because the presidential determination on refugee admissions was delayed, they weren’t able to resettle anyone until early November due to the late setting of the refugee cap.

The Migrant Protection Protocol (MPP), which requires asylum seekers to await their hearings in Mexico, and the asylum ban requiring asylum seekers to seek asylum in the countries they transited through before reaching the U.S. has had a huge impact on Marquez’s work. These policies often force vulnerable refugees to remain in dangerous and unsafe circumstances, often without access to health services and without legal, familial or social support.

Raoul reflected on how asylum has always been difficult to attain for refugees. “The asylum application process is so long, you can be in it for three to five years,” said Raoul. “The limitations that they are trying to impose right now, will affect the people that are crossing the border right now. The people who are in the backlog may have a chance to get asylum, but it is really hard to get asylum, most cases are denied. We don’t encourage people to apply for asylum unless they have a strong case.”

In general, there are five different categories of asylum that people can apply for: political, religious, race, nationality and member of a social group. However, not everyone can qualify for asylum, even if the country of origin isn’t safe to return to for reasons such as war or natural disasters. In the past, people that did not qualify for asylum counted on Temporary Protected Status (TPS), and this status means they won’t be deported. El Salvador and Honduras were among the first countries to be granted TPS in the 1990s, followed by other Latin American countries. However, the Trump administration has attempted to end TPS for the majority of Latin American countries, which was countered by a number of lawsuits, both from federal courts and people affected.

Instead of driving a wedge between U.S. citizens and immigrants, these strict policies are uniting different American organizations fighting for immigrant rights, and encouraging wide-spread civic engagement.

The current situation reminds Raoul of the situation she and co-founder Lily Cerat encountered in 1997 when they pushed for the Haitian Refugee Immigration Fairness Act for 50,000 Haitian refugees whose parole status had run out in Guantanamo. The act, which was passed in 1998, gave them permanent residency.

To Raoul it feels like history is repeating itself. “Now here we are 20 years later, trying to get the same thing for people with temporary protected status,” Raoul said. “Guantanamo prepared us for the border so that we know how to deal with humanitarian paroles and the Haitian Refugee Immigration Fairness Act that passed in 98 for 50,000 Haitians is like the 50,000 TPS holders that we’re working with now.”

Women Refugees

Women’s refugees began to receive more attention in the 1990s, when federal officials pushed the U.S. to reform refugee-asylum law to be more inclusive for women. When the team started their organization in 1992, they were mostly dealing with male refugees. However, one particularly vulnerable, steadily rising group of asylum seekers and refugees are women from Latin America. According to UN Refugee Agency reports, this type of asylum is typically caused by domestic violence.

Raoul attributes this “late” surge of female refugees to the higher liability smugglers connected with women who are more of a risk, especially when they have children. Women are subjected to even greater dangers on their travel routes than men, often experiencing animal attacks, violence and rape.

Women who are subjected to domestic violence used to be considered members of a social group, due to their gender. However, in 2018, former Attorney General Jeff Sessions revoked this categorization for gender-based violence victims, effectively ruling out “private” and gang violence that is not initiated by the state, thus making it nearly impossible for them to gain entry into the U.S.

“The United States used to have a really good refugee act,” New York University and Columbia Professor Sheila Dauer said, “but now the U.S. is backtracking on its recognition that non-state actors can be the perpetrators of various kinds of abuse that qualify as persecution.” Dauer, who was Amnesty International’s Women’s Human Rights Program director for more than 10 years, dealt with the very first asylum case in the U.S., which was eventually approved for domestic violence.

Raoul also spoke about a factor that usually receives less attention—domestic violence is not only something that women have to endure in their countries of origin. Raoul and her organization deal with cases of local domestic violence and abuse as well. They have witnessed a number of cases of male immigrants who return to their home countries to bring in women on a fiancé visa to the U.S. to exercise power upon them, while never actually going through with the process. Her organization has helped these women—and those who experienced gender-based violence in their countries of origin—by hosting peer support groups and connecting them with legal clinics, one-on-one therapy and shelters.

The Trump administration has also threatened to cut off all humanitarian aid for Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, which, among other purposes, has been used towards violence prevention programs. To Dauer, it is a paradox that the Trump administration has reduced funds to combat violence in Latin and Central American countries. “If you don’t want people fleeing to the United States because of violence, why stop sending the funds?” Dauer said.

Richard Jones is a youth and migration advisor, who works for Catholic Relief Services (CRS) and is based in El Salvador. He specializes in addressing violence as a root cause of migration and organizes programs that address violence, especially connected to youth in Central America. CRS also has special programs for women subjected to gender-based violence and programs to stop the cycle of gang recruitment.

Factors Driving Immigration, and How They Can Be Addressed

The CRS program for youth and workforce development has grown to 13,000 members, with a 75 percent rate of success, meaning that after the program the participants got a job, started their own business or went back to school. Similarly, programs designed to address and reduce violence have shown great success and reduced violence by 50 percent in El Salvador and 35 percent in Honduras. All of these gains are now in jeopardy because the administration is enforcing major cuts to foreign aid.

The reduction in aid also means that CRS won’t be able to expand successful CRS funded programs to a wider area of outreach, and programs that were created through governmental funds are either limited or cannot be continued. A program that has not only been cut, but was effectively ended, is a program that prevented child malnutrition and food insecurities in Guatemala, which are key drivers of migration. One of the program’s effects was to cut extreme poverty in half—progress that now may even be reversed in the future.

According to Jones, another policy change that will cause major issues across Latin America is the migration ban that, if enacted will send asylum seekers waiting at the U.S.-Mexican border back to the Latin American countries they transited through.

“By sending more people back here, it is a crisis for the governments, who have very little capacity to deal with the issues,” Jones said, explaining that there will not be enough employees available to process the rise in asylum cases.

Jones also drew attention to a big driver of migration: demographics. Many young people compete for very few jobs, only adding to the driving factors of violence, food insecurity and family reunifications.

However, Jones thinks that the migration crisis at the border can be addressed. “Undocumented migration at the border could be addressed if they [the U.S]would provide greater legal pathways for people who come into the United States,” he said. “That means asylum, family reunification and temporary work visas would help solve the problem. Sending people back here from the border will just put them in greater risk.”

How widespread resistance against the administration’s measures is most obvious through the numerous lawsuits against Trump’s immigration laws. For example, the Ramos v. Nielsen case, which aimed to block the termination of TPS for Sudan, Nicaragua, Haiti and El Salvador.

In dealing with all these burdens immigrants now face, organizations such as Haitian Women for Haitian Refugees and Migration Relief Services, have joined their forces and have a broader support base than ever. Raoul thinks it’s a sign of hope for the future.

“Look at the protests. Look at all the litigation,” Raoul said. “The attorney general associations have so many lawsuits against the Trump administration, that’s gotta be historical. The government is being challenged, and they really can’t handle it.”

Originally from Germany where she completed her BA in English and German Literature and Linguistics, Susanne is now pursuing her Master’s Degree in Journalism and International Relations at NYU. She has always been passionate about writing and reporting and has interned at a local newspaper in Germany and the German-American-Center (DAZ) in Stuttgart. In September 2019, she was appointed New York Transatlantic’s Deputy Editor, and is particularly interested in reporting on climate change and social issues. Besides her passion for journalism, writing and traveling, Susanne loves to cook and post recipes and articles on her personal blog.