Rethinking Western Drug Policies: A Chronicle of Biases and Inconsistencies

What often goes unnoticed is how deeply ingrained these injustices are in Western politics and history. In reality, the failure to reduce the harms associated with drug use long predates Nixon’s War on Drugs. Moreover, the West’s proclaimed intention to tackle these harms is frequently overshadowed by their even stronger inclination to demonize, criminalize, and profit from drug use and addiction.

Image Credit: Think by Numbers

More than 50 years have passed since President Nixon first declared the infamous “War on Drugs” in 1971. However, instead of achieving the eradication of drug use as Nixon had envisioned, the following decades saw the implementation of strict and punitive anti-drug policies and the global intensification of military and police action against drugs.

Ironically, rather than witnessing significant reductions in drug-related harms, the War on Drugs has resulted in a series of consequences. These include a notable rise in mass incarceration rates, heightened levels of inequality along racial and economic lines, the criminalization and stigmatization of addiction, and a surge in rates of addiction and overdose.

A parallel situation can be observed in the United Kingdom’s Misuse of Drugs Act of 1971. Implemented almost concurrently with President Nixon’s declaration of drugs as “public enemy number one,” this Act is believed to have exacerbated the problems associated with drug use rather than reducing them.

More recently, however, Western countries have come to realize that the punitive War on Drugs and responses to addiction simply do not work. This has led to a shift in the nature of their drug policies, placing greater emphasis on public health and harm reduction strategies. Both government and private institutions have now begun to slowly acknowledge their involvement in the War on Drugs and are taking proactive measures to address the numerous injustices that followed.

Yet, what often goes unnoticed is how deeply ingrained these injustices are in Western politics and history. In reality, the failure to reduce the harms associated with drug use long predates Nixon’s War on Drugs. Moreover, the West’s proclaimed intention to tackle these harms is frequently overshadowed by their even stronger inclination to demonize, criminalize, and profit from drug use and addiction.

In my capacity as a drug policy researcher, I regularly encounter questions and criticisms regarding my research area. Considering that legislative frameworks often shape public understanding of these matters, drug policies have played a significant role in creating both structural and attitudinal barriers to research and reform. As such, I feel compelled to explain that, when it comes to drug policies, both the US and the UK have a tendency to blatantly disregard public health considerations and empirical findings in favor of financial and political gains. To illustrate this point, here are three examples.

1. The UK and Cannabis

Since the 1960s, rather than prioritizing treatment, regulation, and drug safety, the UK has opted for punitive drug policies centered around connecting drug use to criminality. The book Drug Science and British Drug Policy: Critical Analysis of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, edited by Professor Emeritus of Addiction Psychiatry Ilana Crome, renowned neuropsychopharmacologist and drug science researcher David Nutt, and Alex Stevens, a Board Member of Harm Reduction International and Professor in Criminal Justice, sheds light on this striking reality. As highlighted, the UK’s drug policies often have little to do with recommendations put forth by advisory councils, doctors, researchers, and social workers. Instead, these policies tend to be influenced by political maneuvering and ambitions. An emblematic example of this disconnect is evident in the treatment of cannabis within the UK’s legislative system.

Unlike other European countries, the UK’s drug policies have seen little to no changes in the past fifty years, and this holds true even for cannabis – the most widely used illegal drug in the UK. Dr. Anne Katrin Schlag, a chartered psychologist and acting CEO of Drug Science, and Professor Nutt delved into this issue in Drug Science and British Drug Policy. Within the UK, cannabis stands out as a drug that has been heavily influenced by politics, sparking debates over its classification, the incorporation of scientific research, and its legalization for medicinal purposes.

However, it is worth noting that the British government has not always been committed to the prohibition of cannabis. Historically, they actually supported its use and even endorsed it while taxing India for their Ganja and Charas sales. This is exemplified by their refusal to support South Africa’s request to have cannabis prohibited at the Council of the League of Nations Advisory Committee on the Traffic in Opium and Dangerous Drugs in 1923, a move aimed at safeguarding their tax revenue from India, which they first enacted in 1798. While they claimed that the taxation was an attempt to reduce cannabis consumption “for the sake of the natives’ good health and sanity,” many believe that the tariff was enacted for its monetary incentives rather than public health concerns.

According to Professor James H. Mills, the Director of Humanities Research at the University of Strathclyde, the British government was compelled to ban cannabis in 1928 after attending the League of Nations’ Second International Opium Convention in 1925. While the global treaty introduced and established during this convention was originally intended to focus on curbing opium use, it went on to include controls over a wide range of other drugs, including cannabis. As emphasized in Professor Nutt’s book, Drugs Without the Hot Air, cannabis was only added to the list of prohibited substances upon the insistence of Egypt. Despite opposition from Britain and India, Egypt claimed cannabis was causing widespread insanity. Many speculate that Egypt’s motivation to demonize and prohibit cannabis may have been an attempt to safeguard its cotton industry from the growing competition posed by hemp cloth – sourced from the cannabis plant’s stem. While their motivations remain subject to debate, the outcome is apparent: Egypt successfully managed to orchestrate and rally support for a comprehensive international embargo on the cannabis trade.

In his book Cannabis Britannica: Empire, Trade, and Prohibition 1800-1928, Professor Mills explains that the British government felt pressured to enforce the ban on cannabis to avoid appearing obstructive to international efforts directed at limiting drug use. To this day, the purchase and use of cannabis remain strictly prohibited in the UK. Nevertheless, there seem to be some inconsistencies and double standards in the way cannabis is treated in the country.

Consider this: while the cultivation of cannabis remains under strict prohibition, with potential legal consequences for offenders, the UK still allows for the purchase, sale, and trade of cannabis seeds. This seemingly minor incongruity serves as a significant catalyst for organized criminal activities and the surge in drug-related convictions – a topic we will delve deeper into in a later piece.

Furthermore, while they legalized cannabis-based products for medicinal purposes in 2018, the practical implementation has fallen short, with the National Health Service issuing hardly any prescriptions at all. The divergence between their policy intent and real-world impact suggests that the estimated 1.4 million individuals who use cannabis for medical purposes still rely on the illicit market. This circumstance is perplexing given that the UK holds the distinction of being the world’s most prominent manufacturer and supplier of medical cannabis. Astonishingly, as confirmed by the UN’s International Narcotics Control Board’s annual report, in spite of the British government’s stance that there is no medical value to cannabis, the UK has assumed the role of primary global producer of cannabis intended for medicinal and scientific purposes.

According to the UN’s annual report, the UK was behind over 70% of the global medicinal cannabis production in 2019, and 43% in 2021. These incongruities—when observing the UK’s willingness to export medicinal cannabis to other nations while its own population of cannabis-dependent individuals is deprived of a regulated supply—demonstrate glaring disparities between the UK’s global actions and domestic cannabis policies that leave its citizens in a challenging predicament with uncertain product quality, potency, and origins. This reflects a level of hypocrisy that warrants serious consideration.

2. MDMA and the Selective Integration of Scientific Research

3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), commonly known as ecstasy or Molly, has sparked intense global debate. Its origins trace back to the laboratories of the German chemical company Merck in 1912, where it emerged as an unplanned by-product during the synthesis of Hydrastinine, a medicine noted for its vasoconstriction and styptic properties. And although it was a product of chance, Merck patented it following their standard synthesis protocols. Notably, despite retaining the patent, Merck chose not to explore the potential for marketing MDMA and eventually distanced itself from the substance.

While some myths suggest the US Army experimented with MDMA in the 1950s, it was not until 1967 that MDMA entered modern research. Alexander Shulgin, a research chemist at Dow Chemicals, rekindled the interest by resynthesizing MDMA and conducting personal experiments on its psychoactive properties, along with several friends. As explained by Emeritus Professor of Psychology at University College London Val Curran, along with Criminology Professor at University of Liverpool Fiona Measham, and Professor Nutt and Dr. Schlag, in Drug Science and British Drug Policy, some of Shulgin’s co-experimenters were psychotherapists, who further explored the effects of MDMA on their patients. They discovered that the substance significantly improved their patients’ ability to communicate and achieve greater insight into their mental health struggles and challenges.

Shulgin also continued his legal research of MDMA and its effects on the brain and behavior. However, marketing a substance is an incredibly lengthy and costly process that is only worthwhile for companies if they have exclusive rights to the substance. Regrettably, this lack of financial incentive dissuaded pharmaceutical companies from pursuing MDMA, as it had already been patented by Merck. Consequently, only a handful of therapists and researchers had the opportunity to explore MDMA’s therapeutic benefits, leaving individuals grappling with mental health issues and traumas with little choice but to resort to highly addictive – and conveniently more profitable and taxable – antidepressants. Nonetheless, during the 1970s and early 80s, MDMA began gaining popularity as both a therapeutic and recreational drug.

Despite protests from therapists and psychiatrists, MDMA was classified and prohibited as a Schedule I drug in 1985. Under the DEA’s classification, Schedule I drugs are “defined as drugs with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.” However, given its well-established therapeutic benefits, the classification’s basis seems to lie more in MDMA’s lack of profitability and tax revenue generation than its purported risks. Furthermore, its Schedule I designation solidified MDMA’s status as a sought-after recreational drug, contributing to a rapid surge in its usage within the US. In an effort to suppress and stigmatize the use of MDMA – a drug deemed to be untaxable and an interference with other pharmaceutical drugs – Sen. Bob Graham (D–Florida) introduced the Ecstasy Anti-Proliferation Act of 2000 and later the Ecstasy Prevention Act of 2001.

While the Anti-Proliferation Act amended the Federal sentencing guidelines, imposing harsher penalties and promoting “aggressive law enforcement action” for MDMA-related offenses, the Prevention Act went even further, actively seeking to stigmatize MDMA through selective and biased scientific research. With the Ecstasy Prevention Act, the US government completely disregarded any potential therapeutic benefits of MDMA and instead allocated funding to studies solely focusing on uncovering the harms associated with its use. Most notably, it mandated the Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse to conduct a research study that exclusively examined the negative effects of MDMA on individuals’ health. As argued by Professor Curran et al., not only were the possible benefits of MDMA overlooked, but they were also unjustly deemed not worthy of further investigation, in spite of the initial positive reports from psychotherapists in the 1970s.

However, after an extensive research hiatus, studies have consistently shown MDMA to rank relatively low in terms of harm to both people and society, especially when compared to other drugs and substances. According to Professor Nutt, Dr. Leslie King (an expert adviser to the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction), and Dr. Lawrence Phillips (an Emeritus Professor at the London School of Economics & Political Science), alcohol poses the greatest harm to people and society, followed by heroin and crack cocaine. Nevertheless, when Professor Nutt publicly acknowledged that their research findings indicated ecstasy to be safer than alcohol, he was asked to resign from his role at the UK’s Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs and was accused of encouraging drug use. The complete disregard and distortion of scientific evidence by the British government, as well as the prohibition of MDMA, its classification as a Schedule I drug, and implementation of the Ecstasy Anti-Proliferation Act of 2000 and the Ecstasy Prevention Act of 2001 in the US, underscore how political interests tend to override empirical research findings in drug policy decisions.

Additionally, these policies have only served as barriers to investigating the potential health benefits of MDMA. Contrary to the government’s claims and fears, research has shown that MDMA poses limited harm and is considered safe, non-addictive, and an increasingly viable therapeutic tool. Several empirical studies have already begun experimenting with MDMA to treat challenging conditions like alcohol dependency, severe post-traumatic stress disorder, and anxiety, yielding promising results. Given the growing number of supportive studies, it is clear that MDMA deserves further investigation and should be legalized for medical purposes, rather than maintaining its Schedule I status in the US and its Class A status in the UK.

3. Anti-Drug Laws and Targeting Immigrant Communities

Over the last two decades, the opioid epidemic has devastated the lives of hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of people across the US. Despite opium’s criminalization over a century ago in 1914, the rate of opioid use and overdoses have continuously escalated each year. As time has gone by, it has become increasingly apparent that systemic racism, societal inequality, and stigmatization have played a huge role in both the foundation and formation of drug policies in the US. Indeed, their earliest anti-drug laws were motivated less by combating opium use and more by racial prejudice, and the marginalization and stigmatization of Chinese immigrant communities.

As detailed by English writer Martin Booth in his 1999 book Opium: A History, opium was first commercialized in 1803 when a German pharmacist successfully isolated its active ingredient, naming it “Morphine” after Morpheus, the Greek God of dreams. Subsequently, the pharmaceutical company Merck undertook the mass production and global distribution of morphine. As opium became widely available in the US, instead of resisting it or associating it with societal issues, Americans valued morphine for its medicinal properties, including pain relief, fever suppression, and anti-diarrhea capabilities.

Simultaneously, the discovery of gold in California during the 1840s triggered a massive wave of immigration from China, driven by their dire economic circumstances. By 1870, around 63,000 Chinese immigrants had arrived in the US with an astounding 77% settling in California. This influx intensified local labor competition, which then in effect escalated racial tensions and widespread discrimination against the Asian communities. Consequently, California saw the implementation of discriminatory ordinances, such as the Foreign Miners License Tax Act of 1852, selectively imposing a four-dollar monthly fee on foreign laborers – a provision disproportionately enforced against the Chinese. Further entrenching the divide, the Chinese Police Tax Law of 1862 levied a monthly tax exclusively on adults of the “Mongolian race” engaged in mine work or hired by most businesses. In a further display of biased targeting, the government employed the prohibition of the Chinese cultural tradition of opium smoking as another means to marginalize Chinese immigrants.

Dr. Daniel Arendt, an Assistant Professor of Pharmacy Practice and Administrative Sciences sheds light on the surge in opium addiction, popularly known as the “soldiers’ disease,” following the extensive use of morphine during the Civil War. However, drug historian David Courtwright disagrees with the notion that the majority of those addicted were soldiers and believes this to be a misleading nickname. Instead, he explains that around 60% of opioid-dependent individuals post-Civil War were reportedly women. The reason for this stark gender difference can be attributed to the widespread prescription of opioids to women, particularly White upper-class women, in the 19th century.

Courtwright explains that, at the time, men “were expected to bear pain more stoically. They were not expected to seek out doctors for every ache and pain.” Women, on the other hand, faced a contrasting reality. Medical professionals frequently prescribed morphine to women for various ailments, including minor headaches, menstrual cramps, uterine and ovarian complications, and even the controversial diagnosis of hysteria. According to Dr. Arendt, this pattern of overprescription, coupled with the opioid dependency that followed the Civil War, led to a sharp rise in opioid addiction and overdoses.

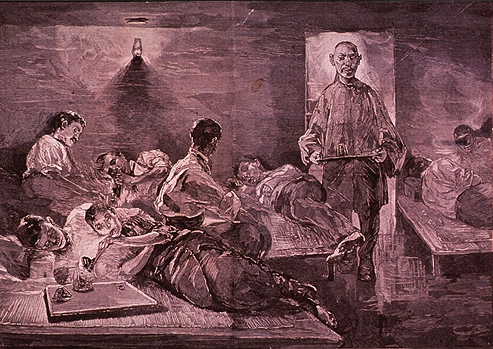

As addiction rates soared across the US, medical practitioners curtailed the prescription of opioids for minor pains and ailments. This drove opioid-dependent individuals to seek alternative sources, leading them to opium dens commonly found within Chinese immigrant communities. Psychiatrist David F. Musto, an expert on US drug policy and the War on Drugs highlighted that public perception of opium only began to shift after it became increasingly associated with Chinese immigrants. As this association deepened, a growing number of Americans came to regard opium smoking as a threat to their established Eurocentric ideals and moral fabric.

Dr. Arendt’s research similarly depicted this phenomenon, revealing that when affluent white women began frequenting Chinese opium dens, it catalyzed a surge in racial tensions. This unsettling development prompted the government to exploit ethnic scapegoating and racially driven fearmongering, effectively stoking the flames of anti-Asian discrimination and racism. The Chinese immigrant community found themselves unfairly depicted as uncivilized through these manipulation narratives.

As detailed by William L. White, a prominent author and historian specializing in addiction treatment and recovery, the government then proceeded to outlaw the smoking of opium through the enactment of the San Francisco Opium Den Ordinance of 1875. The very first of its kind, this Ordinance rendered it a misdemeanor to maintain, visit, contribute, or endorse any establishment where opium is smoked. Of significance is the fact that this statute did not encompass the prohibition of opium’s importation, possession, or use – measures that would have disproportionately impacted affluent Chinese and European importers and suppliers, as well as the opium-dependent individuals from well-off White demographics. Instead, the focus remained steadfast on opium dens and the act of opium smoking. Through this strategic alignment, the first anti-drug law in the United States pinpointed its intentions, honing in solely on establishments exclusively operated by Chinese proprietors within Chinese immigrant communities.

According to White, the ripple effect of the San Francisco Opium Den Ordinance extended into a series of racially motivated drug laws, with 11 Western states following suit and enacting anti-opium legislation between 1877 and 1900. However, the discriminatory employment of drug policy to target racial minorities goes beyond the Chinese immigrant population affected by opium prohibition. This pattern was also exemplified by the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914, the US’ first anti-cocaine law, which effectively curtailed the nonmedical utilization of opium and cocaine while predominantly singling out Black communities.

Eminent psychologist and neuroscientist Dr. Carl L. Hart points out that the timing of the Harrison Act coincided with a period when both the government and the media were portraying Black communities as “negro cocaine fiends.” An illustration of this bias can be found in a 1914 New York Times article, titled “NEGRO COCAINE ‘FIENDS’ ARE A NEW SOUTHERN MENACE,” wherein a distinguished physician claimed that escalating murder rates were attributed to “cocaine-crazed negroes” who “have taken to ‘sniffing’ since deprived of whisky by prohibition.” In a similar vein, during the congressional hearings surrounding the Harrison Act, experts testified that “most of the attacks upon white women of the South are the direct result of a cocaine-crazed Negro brain.”

Another example is the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, the first federal cannabis law. As argued by Robert Solomon, the Co-Chair of the UCI Center for the Study of Cannabis and Clinical Professor of Law, the formation of the Marihuana Tax Act appears to lack foundation in scientific exploration, serious policy contemplation, or even ethical considerations. Instead, Solomon contends that the motivation for the Act was fueled by “racism, sensationalism, and social control of racial minorities.”

The driving force behind the anti-cannabis crusade was Harry Anslinger, the first commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, whose influence was pivotal. Anslinger adeptly popularized the term “marihuana” diverging from the prevalent term “cannabis,” a strategic maneuver that connected the substance to prejudiced sentiments against Mexicans. Unashamedly, Anslinger’s stance bore no concealment of his prejudicial leanings against minority groups. In a letter shared with Congress, he brazenly asserted, “I wish I could show you what [marijuana]can do to […] degenerate Spanish-speaking residents.”

His sentiments were perhaps best encapsulated in his notorious declaration:

There are 100,000 total marijuana smokers in the U.S., and most are Negroes, Hispanics, Filipinos and entertainers. Their Satanic music, jazz and swing result from marijuana use. This marijuana causes white women to seek sexual relations with Negroes, entertainers and any others.

Overall, these instances serve as mere glimpses into the array of drug laws that demonstrate a repeat cycle of racially prejudiced policies, systematically marginalizing and disenfranchising minority populations. These vignettes demonstrate how the pursuit of public health and scientific inquiry is often subdued by a pattern of policymaking that perpetuates greater harm, exacerbates inequalities, and amplifies discrimination.

After having experienced well over a century of widespread stigmatization and criminalization of drugs and addiction, the resounding conclusion seems clear. The punitive War on Drugs has proven itself a failure, fostering more problems than solutions. With increased rates of drug use, overdose, drug-related offenses, and imprisonment, these staggering consequences call for reform and transformation. It is now time to prioritize public health and move away from zero-tolerance policies towards harm reduction strategies aimed at curbing addiction and overdose rates, increasing drug safety and education, and expanding access to treatment and recovery services.

Nicky Kashani is a criminology and psychology graduate, and current masters student at NYU. Her research interests are drug policies, stigmatization, and labeling. For her undergraduate dissertation, she conducted a preliminary investigation of Oregon’s drug policy reform, and assessed the processes, benefits, and adverse effects of the decriminalization of illicit drugs. More recently, she has discovered a passion for journalism and has begun writing about current events in Iran. She is also an assistant editor at Caustic Frolic, an interdisciplinary journal that publishes fiction, nonfiction, poetry, art, and digital and mixed media. She looks forward to further pursuing journalism in the near future.