Kent State Massacre’s Twin: 40 Years Later and 8000 Miles Away, Why Don’t We Care?

Women march in Papua New Guinea after police shoot at protesting university students. Image via Loop News.

On June 7, Papua New Guinea’s police opened fire on university students who were peacefully protesting against government corruption. Initial reports stated that four students died, and nine others were injured, though the Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea, Peter O’Neill, denies any fatalities.

Sound familiar? It might be because we have heard this before.

On May 4, 1970, the Ohio National Guard at Kent State University shot and killed four students, and injured nine others, when responding to protests against President Richard Nixon and the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War. The event, which has since been deemed the Kent State Massacre, ignited a wave of protest across the country. To this day, none of the National Guardsman involved have been convicted for the shooting.

Though separated by more than 40 years and 8,000 miles, the events in Kent State and Papua New Guinea follow a similar pattern: a long brewing dissatisfaction with government catalyses student protests, which is then met with violence from state forces, which is then vehemently denied by government leaders, and consequently heightens student ire leading to civil unrest and vandalism. Yet, while the shootings in Kent State sparked global outrage and condemnation, leading to protests in 450 campuses across America, the two-month long protest in Papua New Guinea is drawing little attention.

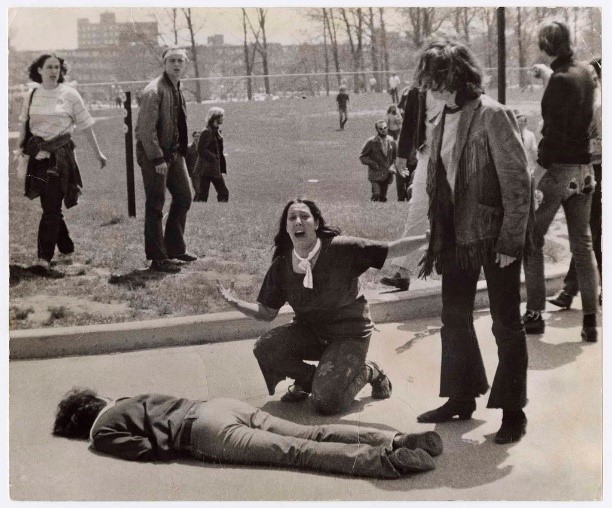

The infamous Pulitzer prize-winning image of fourteen-year-old Mary Ann Vecchio, mouth contorted in grief, kneeling over a student shot by police in Kent State, remains forever singed in our memories. It became a defining image of the Vietnam War and its effects on Americans.

The shooting at the University of Papua New Guinea has similarly generated many provocative images—perhaps none more so than that of two dozen women marching through Port Vila, hands over their heads, with mud rubbed on their faces and bodies as a symbol of mourning. It is a further tragedy that their demonstration should be so widely ignored by the international community.

Papua New Guinea, a former colony of Australia who won independence in 1975, seldom makes international news. When it does, reports usually center on fantastical accounts of cannibalism and witch killings, rarely acknowledging the modern political challenges which underpin such violence. As a result, attempts at political reform in Papua New Guinea are often made invisible or downplayed on the international stage. But, it is striking that the shootings against Papua New Guinea today are so widely ignored, especially given its similarities to the Kent State Massacre which once gripped America.

Like American students, Papua New Guinea’s youth are politically articulate and desperate for change. The shootings, just as was the case in 1970s America, reveal the risk this class of educated youth poses to state leaders, whose legitimacy sits in precarious balance.

Since 2014, the National Fraud and Anti-Corruption Directorate has attempted to arrest Papua New Guinea’s Prime Minister Peter O’Neill on charges of corruption. As one commentator noted, this two-and-a-half-year battle to bring O’Neill to justice has exposed the “Shakespearean proportions” of misdemeanor committed by his government. His office has been implicated in mismanagement, fraud, and shady international dealings. This culminated in the arrests of Papua New Guinea’s Attorney General Ano Pala, the Supreme Court Justice Bernard Sakora, and the prime minister’s lawyer, Tiffany Twivey Nonggorr on charges of corruption and perverting the course of justice.

Despite the arrests of those close to him, O’Neill continues to evade the courts and further investigations into his dealings. In October last year, the government suspended the Chief Magistrate Nerrie Elikim, who had first issued an arrest warrant against O’Neill. The Department for Immigration similarly banned two Australian lawyers preparing the corruption case against the prime minister from entering Papua New Guinea for unknown reasons. By using the courts to dispute his arrest warrant, and aligning a tangle of loyalists to flout any further attempts to bring him to trial, O’Neill retains a silent impunity.

It may be easy to dismiss the current violence and protests in Papua New Guinea as distant outcome of the state’s ‘underdevelopment,’ where instability, government corruption and violence are commonplace. But, to do so would to ignore the experience of those protesters in Kent State, who found that violence and injustice shows no geographic discrimination.

The protests, which ignited American cities in the 1970s following the Kent State shooting, revealed to the world that confronting political injustice is not only a civic right, but integral to ensuring political accountability. Their violent repression was utterly inexcusable.

Yet today, protesters in Papua New Guinea continue to fight in vain, while few outside the country listen. Australia, which provides the most aid and investment to Papua New Guinea, has not yet condemned the government’s actions, simply calling for a de-escalation of tensions. And, as a further blow, last week the University of Papua New Guinea decided to suspend the 2016 academic year on account of the protests, demanding all students leave the campus by the end of the week.

Accusations of unequal outrage toward similar international tragedies are nothing new, of course. It has become almost ubiquitous to shout hypocrisy when deadly attacks on American soil garner more attention than those frequently occurring abroad. But it deserves repeating: when we dole out compassion based on citizenship rather than an understanding of injustice, we not only disparage the rights of those activists today, but we also disparage the memories of those who fought for the same freedoms before them.

Prianka is an Australian journalist based in New York. She is currently enrolled in NYU’s joint Masters Program in Journalism and International Relations. Prior to this, Prianka worked as a Community Development Project Officer at the Asylum Seeker Welcome Centre, an organization that provides educational and social support for asylum seekers living in the Melbourne community. She also spent a year in Vanuatu, serving as a Community Project Officer with the Marae Village Development Council.