Why Do Cease-Fire Agreements Mediated by Third Parties Fail?

The remains of a market in Maarat al-Noaman, in Syria’s northern province of Idlib, after an airstrike Tuesday. Dozens of people were reported killed. | Photo courtesy Mohamed Al-Bakour/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

The remains of a market in Maarat al-Noaman, in Syria’s northern province of Idlib, after an airstrike Tuesday. Dozens of people were reported killed. | Photo courtesy Mohamed Al-Bakour/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

Why are cease-fire agreements mediated by third parties likely to be short-lived? An examination of recent events in Syria can provide us with useful insights.

On March 18, 2011, Syrian policemen arrested some children for drawing politically charged caricatures on a wall in the city of Dara’a. On the same day, thousands of citizens held demonstrations in the streets to demand the release of the children, with six people killed by police fire. The demonstrations spread to big cities such as Aleppo, and President Bashar al-Assad responded with repressive action. On January 2, 2013, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, an NGO based in London, announced that more than 60,000 people were killed since big demonstrations began in 2011.

Great powers took a variety of measures against the repression of the Assad administration, making efforts to achieve cease-fire agreements between the Syrian government and major opposition groups such as the Free Syrian Army. For instance, on August 18, 2011, U.S. President Barack Obama demanded the resignation of President Assad. On August 19, EU countries also demanded his resignation. Then on September 2nd, the EU decided to ban all imports of Syrian oil.

In order to work closely together, the former Secretary General of United Nations, Kofi Annan took the lead and the five permanent members of the UN Security Council and representatives of EU and the League of Arab States, issued a joint communiqué on June 30, 2012. Due to the ongoing Geneva Peace Talks that had continued in several iterations from 2012 to 2016, on February 23, 2016, the Syrian government and a major opposition group announced that they would observe a conditional pause in the fighting.

Finally, after intensified fighting and a vow by Bashar al-Assad to retake the entire country, a cease-fire negotiated by Russia and the United States officially took effect on September 12, 2016. At first, the United States supported an alliance of rebel groups and Russia supported Bashar al-Assad. Both countries, however, shared common enemies such as the Islamic State and the Nusra Front fighters who had seized parts of Syria, making it a magnet for jihadists.

History, unfortunately, has demonstrated that cease-fire agreements mediated by third parties like this one tend to be broken soon. For instance, the breakout of the cease-fire agreement between Israel and Hamas in 2014 is still fresh on our minds. As we can see, Syria is no exception. On April 19, 2016, government warplanes attacked protesters in the northwestern Syrian town of Maarat al- Noaman, killing dozens of people. This attack illustrated the fragility of the cease-fire agreement between Syrian government forces and some armed opposition groups. Moreover, on September 19, soon after the cease-fire agreement between the United States and Russia took effect, a humanitarian aid convoy was also attacked. As a result, the Syrian military declared that a seven-day partial ceasefire was over and immediately began intensive bombardments of rebel-held areas in Aleppo.

Why does this happen—why are cease-fire agreements mediated by third parties so short-lived? I will clarify the reason below by using game theory to model the Syrian situation.

Game theory is the study of strategic interdependence through modeling situations as games with multiple players. In these games, each player’s actions affect both their welfare and the welfare of all other players, and vice versa. Game theory models the outcomes that will occur if all players choose their best responses by choosing the action that will maximize their net gains, given that all other players will also choose their best responses. In other words, the outcomes represent an intersection of optimal choices made by all the players. In the game below, I will focus on the situation that arises after third parties intervene in civil wars.

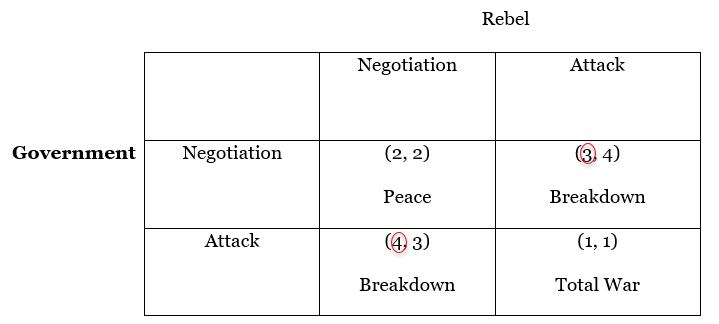

First, I summarize the preferences of both the Government and Rebel in the chart below:

There are three types of outcomes: peace, breakdown and total war. First, if both players choose to negotiate, they can reach a cease-fire agreement and achieve peace. Second, cease-fire agreements break down if one of them chooses to negotiate, while the other chooses to attack. In this case, either player breaks the cease-fire agreement and attacks the other unilaterally. Finally, total war breaks out if both players choose to attack.

The preferences of both players are shown in parentheses: the numbers on the left-hand side of the parentheses represent the payoffs of the Government, while the numbers on the right-hand side represent the payoffs of the Rebels. In game theory, payoffs are the numerical representation of the benefits each player will receive from choosing an action. Therefore, the players’ preferences in this game can be presented as follows: Breakdown (Attack) > Breakdown (Attacked) > Peace > Total War.

The reason Breakdown (Attacked) is the second-best preference is because third parties guarantee the security of both parties by stationing their troops or mediating them. Barbara Walter, a professor at the University of California San Diego, argues that all combatants are concerned that after a cease-fire agreement, the opposition will betray the terms and attack them one-sidedly again. As a result, they are caught unprepared and are significantly damaged. Thus, she argues, third parties should station their troops in order to alleviate the combatants’ fears and to achieve cease-fire agreements. However, I argue that all combatants attempt to make use of the security guarantees provided by third parties in order to attack the opposite groups one-sidedly because they stand to lose less by striking first.

Moreover, both sides can gain only (2, 2) if both choose to negotiate and achieve peace. This is because third parties might impose power-sharing on the parties against their will at the negotiation table; this will not allow both the parties to exert their own will even if they achieve peace. Therefore, they can gain only (2, 2) even if both choose to negotiate and achieve peace. However, it is observed that these parties prefer to continue fighting with security guarantees provided by the third parties rather than having the major burden of power-sharing imposed at the negotiation table.

First, we will look at the optimum choices of the Government. Suppose that the Rebels choose Negotiation. In this case, Attack is optimal for the Government because 4 is larger than 2 out of their two options. Suppose, however, that the Rebels choose Attack. In this case, Negotiation is more optimal for the Government because 3 is larger than 1. Therefore, we can show the optimal choices of the Government in the chart below:

In the same fashion, we can find out the optimal choices of the Rebel, and show them in the chart below:

Therefore, the outcomes of this game where both players would end up are (Attack, Negotiate) and (Negotiate, Attack). These both lead to Breakdown as an outcome; even if one side is ready to negotiate and disarm, the other side attempts to betray and attack again:

Therefore, the outcomes of this game where both players would end up are (Attack, Negotiate) and (Negotiate, Attack). These both lead to Breakdown as an outcome; even if one side is ready to negotiate and disarm, the other side attempts to betray and attack again:

In general, a game with such structure is called a “chicken game,” because both players have their respective escape routes; however, if one of them chooses to escape, then the other gains the most. On the other hand, if neither side chooses to escape, then both the parties face significant losses. In this case, both the Government and the Rebels have their respective escape routes and chances to disarm; however, if either of them chooses to disarm, while the other does not, then they possess less of an advantage compared to the other player. If neither of them chooses to disarm, then both face significant damages. Therefore, they reach a “Breakdown” in this game, in which either side breaks the cease-fire agreement and starts the fight again.

In general, a game with such structure is called a “chicken game,” because both players have their respective escape routes; however, if one of them chooses to escape, then the other gains the most. On the other hand, if neither side chooses to escape, then both the parties face significant losses. In this case, both the Government and the Rebels have their respective escape routes and chances to disarm; however, if either of them chooses to disarm, while the other does not, then they possess less of an advantage compared to the other player. If neither of them chooses to disarm, then both face significant damages. Therefore, they reach a “Breakdown” in this game, in which either side breaks the cease-fire agreement and starts the fight again.

This is how interventions by third parties end up prolonging civil wars. Third parties provide both power-sharing and security guarantees for the two sides; however, both the government and rebels make use of the security guarantees that third parties provide for them to escape from the burden of power-sharing. This demonstrates that the security and power-sharing guarantees that third parties provide for combatants do not enable the cease-fire agreements to last a long time.

We can call this a “commitment tragedy,” because third parties attempt to commit to civil wars in order to alleviate combatants’ fears; however, combatants actually make use of the security guarantees that third parties provide for them in order to take power after the conflicts. As a result, cease-fire agreements break down. Even now, both the United States and Russia are negotiating bitterly over the future of Syria. The results of these negotiations, however, remain to be seen.

Kazumichi Uchida received a Master of Arts degree from Keio University in Japan and New York University in March 2010 and May 2016, respectively. His majors are International Relations and Security Studies.

It sounds like, if we can estimate and manipulate the payoffs for each side, third parties can possibly find solutions to conflicts that create peace among all sides. I would guess each side would have to police themselves to avoid future conflict. The peace then needs to be seen as more valuable than whatever could be gained through conflict. Unfortunately, I don’t think third parties that have a biased interest in the outcomes are effective at finding a peaceful solution to the more local problems that are at the core of the conflict. Maybe this is a role for a third party NGO?